That President Trump has the authority to vacate the actions of his predecessors is without question. Just as no Congress can bind a future one, no president—with a unilateral decree—can claim to rule forever. That is even more the case given that Clinton and Obama far exceeded their authority under the Antiquities Act. Nonetheless, revocation will be fought aggressively by radical environmental groups and will require the Solicitor General to defend revocation before the Supreme Court of the United States, but it is the right thing to do.

Opinion by William Perry Pendley, Esq. President, Mountain States Legal Foundation

President Trump has a unique opportunity to make tangible his concern for forgotten Americans, increase employment—including high-paying coal miners—and defend the rule of law, separation of powers, and the Constitution. In the process, he will rob President Obama of his sole surviving legacy, one that will bedevil rural people in perpetuity to the utter delight of environmental groups, one of which cosponsored the “Women’s March.” He can do all this simply by vacating two national monuments by Obama in 2016 and an especially egregious one by President Clinton in 1996.

The Antiquities Act of 1906, which allegedly provides authority for these vast decrees, was never intended for that purpose. Instead, Congress sought to protect “historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest,” what the House of Representatives report called “interesting relics [‘ruins’] of prehistoric times” that are “scattered throughout the [American] Southwest [on] public lands.” Initially, designations were limited to “320 to 640” acres, but finally provided for “the smallest area compatible with the proper care and management of the objects to be protected.” As early as 1911, federal officials resisted efforts by “patriotic and public-spirited citizens” to designate monuments for “scenery alone” because the Act does “not specify scenery, nor remotely refer to scenery as a possible raison d’etre for a public reservation.”

Presidents Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin Roosevelt, and Jimmy Carter exceeded their statutory authority in frequent uses of the Act, but their actions—some of which were modified by later presidents or made the subject of congressional designations—occurred before public land law’s modern era. That began in 1976 with passage of a federal law by which Congress reasserted its exclusive authority over federal land under the Property Clause in a belated response to a Supreme Court ruling that it had acquiesced in the Executive’s usurpation of that power. Thereafter followed decades of enactments by which Congress provided for the protection of “wild and scenic rivers,” “wilderness areas,” “endangered or threatened species,” and other concerns, each of which required an act of Congress and signature by the president. Congress left the Antiquities Act standing, theoretically limited to its original purpose, and that is the way it was viewed by Presidents Reagan and George H.W. Bush, who issued no decrees.

Not so Clinton who among his many Antiquities Act edicts, closed one of the world’s best low-sulfur coal deposits—its mining will create 1,000 local jobs and generate $20 million annually—with the Escalante-Grand Staircase National Monument. So passionate was Utah’s opposition to the monument that Clinton deceived political leaders—but not Robert Redford—about his plan until he announced it at Arizona’s Grand Canyon. Today, Garfield County is a self-declared “economic disaster” area.

Likewise, Obama ignored unanimous State and local opposition in Maine and used the Act to designate 87,654 acres purchased for the National Park Service (NPS) as a “seed” for the NPS’s 1988 plan for a 3.2 million acre park contrary to a 1998 federal law requiring that Congress authorize all new park suitability studies. Finally, in a belated Christmas gift to Leonardo DiCaprio and other environmental extremists, Obama thumbed his nose at all Utahans with his 1.35 million acre Bear Ears National Monument in San Juan County.

That President Trump has the authority to vacate the actions of his predecessors is without question. Just as no Congress can bind a future one, no president—with a unilateral decree—can claim to rule forever. That is even more the case given that Clinton and Obama far exceeded their authority under the Antiquities Act. Nonetheless, revocation will be fought aggressively by radical environmental groups and will require the Solicitor General to defend revocation before the Supreme Court of the United States, but it is the right thing to do.

Meanwhile, Congress should repeal the Antiquities Act to prevent lawlessness by any future president who views rural Americans with disdain.

Free Range Report

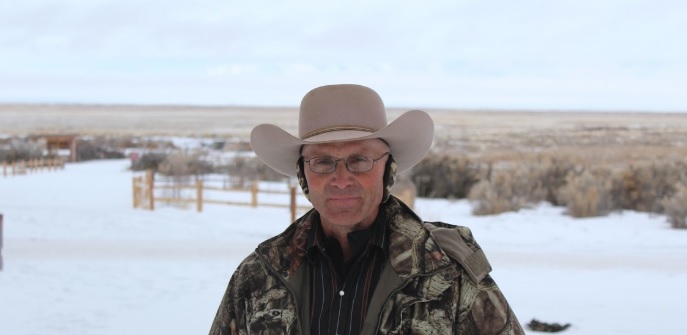

Please let all these Patriots free. Give us our land back. Get rid of BLM.

That a president can vacate an Antiquities declaration certainly is under question. The wording of the law refers to designating monuments, but does not refer to reversing such a designation. The Antiquities Act consists of Congress delegating it’s authority to the president. So unless the law explicitly authorizes reversing a previous declaration, which it doesn’t, it is a reasonable claim that only Congress can reverse it, because in the wording of the act, Congress only delegated the authority to dsignate.