Recent presidents have all but ignored important stipulations in the Antiquities Act that are supposed to restrict the president’s power in key ways. The law dictates that monuments must be sites of historic or scientific interest and cannot exceed “the smallest area compatible with the proper care and management of the objects to be protected.”

Op-ed by Randy T. Simmons, Jordan K. Lofthouse

Antiquities Act review a chance to scale back executive overreach

President Trump’s review of recently created national monuments, especially the 1.3 million-acre Bears Ears National Monument, is a unique opportunity to reflect on the uses and abuses of the Antiquities Act. The Bears Ears designation is a cautionary tale of the nearly unlimited power of the president and how that power affects real Americans.

Reviewing the Bears Ears designation opened a vicious debate in Utah and across the country. One side has decried the review, stating that a challenge to a national monument desecrates America’s federal lands. Another side argues that national monuments harm local people and economies without the locals’ consent. Though both these arguments are worth consideration, a more fundamental concern is the unchecked power given to presidents through the Antiquities Act.

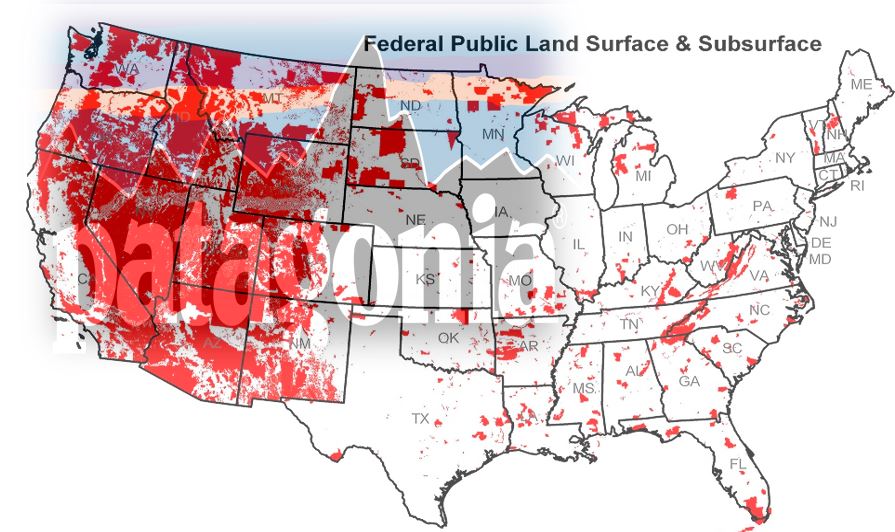

The Department of the Interior’s review, especially of Bears Ears, should be used to restrain the unchecked executive power that has led to many of the national monuments we have today. The Antiquities Act gives presidents the ability to unilaterally designate federal land as a “national monument.” It was originally intended to prevent the destruction of well-defined sites in immediate danger, such as Devils Tower, the first national monument. The act allows the president to bypass Congress for the sake of protecting at-risk land quickly. But without meaningful checks and balances, presidents have abused the act to designate multi-million acre tracts of land as monuments. Past abuses of the Antiquities Act cannot justify continuing abuses.

[wp_ad_camp_1]

Recent presidents have all but ignored important stipulations in the Antiquities Act that are supposed to restrict the president’s power in key ways. The law dictates that monuments must be sites of historic or scientific interest and cannot exceed “the smallest area compatible with the proper care and management of the objects to be protected.”

Bears Ears does include a few sites of legitimate historic and scientific interest, but plenty of desert indistinguishable from the rest of the Four Corners region is contained in its 1.3 million acres. President Obama’s proclamation establishing the monument included musings about the presence of sagebrush, mule deer, pine trees and rabbits.

Many of Obama’s justifications for Bears Ears could just as easily be used to designate the entire Colorado Plateau. If Bears Ears National Monument actually fit the intent of the Antiquities Act, it would be limited to a few square miles around the Bears Ears mesas with additional carve outs for the assorted historic sites scattered throughout the area.

Several past presidents have used the Antiquities Act to establish an environmental legacy, but such designations are inconsistent with the act, are an overreach of executive power, and undermine checks and balances. Because presidents can establish national monuments with the stroke of a pen, the Antiquities Act is an easy way for presidents to build those legacies. National monuments are popular with the general public, but they are often opposed by the people who live near them. Obama designated Bears Ears during the lame duck period between the 2016 election and the inauguration, which was an obvious attempt to minimize blowback from the controversial decision. The timing and size of the designation strongly suggest that designating Bears Ears National Monument served mainly to pad Obama’s environmental legacy.

National monuments, parks and wilderness areas hold a special place in Americans’ hearts. We love preserving our national heritage, but the power to protect federal lands should come with appropriate constraints. Although previous presidents have used the Antiquities Act imprudently, the current review of national monuments is a good chance to scale back past overreach and reflect on the indiscriminate power given to the president.

Randy T. Simmons is a professor of political economy at the Jon M. Huntsman School of Business at Utah State University and is president of Strata. Jordan K. Lofthouse is a Strata Ph.D. fellow.