“In the nearly fifty years since it was signed into law, the ESA has done more to impede economic activity, obstruct local conservation efforts, and give federal bureaucrats regulatory control over private property, than it has done to protect endangered species.”

by Marjorie Haun

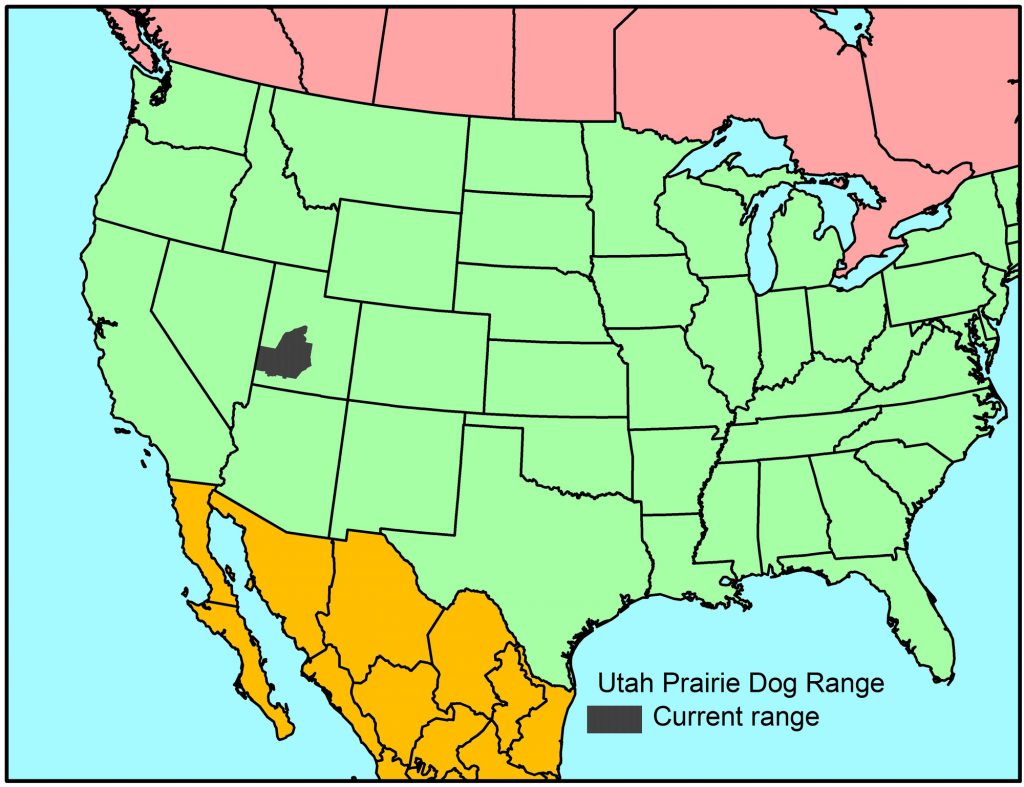

The fight over the Utah prairie dog appears to be headed to the U.S. Supreme Court. The rodent, a subspecies of the ubiquitous American prairie dog, exists primarily in one area of southwestern Utah. The region, covering Beaver, Iron and Washington Counties, is also primarily private agricultural property, so the clash between farmers and ranchers, and colonies of field-burrowing critters is inevitable.

Environmentalist groups, as well as the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Department, are fighting to keep the Utah prairie dog on the federal endangered species list. Initially listed in 1973 as ‘endangered,’ the rodents were reclassified in 1984 as ‘threatened,’ and with a population of 82,000, mostly on private property in a region of Utah, questions abound about who has jurisdictional authority over their protection.

A group of property owners calling itself ‘People for the Ethical Treatment of Property Owners (PETPO),’ is reversing the narrative in southwestern Utah by playing on the title of a radical ‘animal rights’ group, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA). Pacific Legal Foundation (PLF) is taking up the case of PETPO, and it appears this case could have national implications because the position of PETPO is that the federal government has no authority over a species which exists entirely within the borders of one state. Calling into question the federal government’s application of the Commerce Clause to implement interstate regulations, PLF is making the point that the Utah prairie dog is an ‘intrastate’ species, and is therefore not subject to the Endangered Species Act (ESA). In its petition to the Supreme Court, PLF states:

This case presents vital and persistent constitutional questions about Congress’ power to regulate intrastate, non-economic activity under the Commerce Clause and Necessary and Proper Clause…

Under the Endangered Species Act, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service adopted a regulation prohibiting the “take” of Utah prairie dogs on private property. The district court struck down the regulation as exceeding the Commerce Clause because: it regulates intrastate, non-economic activity with no substantial effect on interstate commerce; and the species resides in only one state and has no significant connection to interstate commerce.

With a potential impact on federal endangered species regulation, and the inescapable battles that will ensue as other parties and states follow PETPO’s lead, Utah’s senators want to settle the debate by taking it out of the courts and putting it into law. On September 16, Utah Senators Mike Lee and Orrin Hatch announced their introduction of the Native Species Protection Act (SB1863), a bill that would give states jurisdiction over endangered species which exist solely within their borders, and as in the Utah case, on private property. Its summary reads:

S.1863 – A bill to clarify that noncommercial species found entirely within the borders of a single State are not in interstate commerce or subject to regulation under the Endangered Species Act of 1973 or any other provision of law enacted as an exercise of the power of Congress to regulate interstate commerce.

Senator Mike Lee also issued a press release citing flaws in the Endangered Species Act and the need for reform, as well as the importance of this legislative fix to intrastate endangered species regulations:

“In the nearly fifty years since it was signed into law, the ESA has done more to impede economic activity, obstruct local conservation efforts, and give federal bureaucrats regulatory control over private property, than it has done to protect endangered species. The Native Species Protection Act is a commonsense reform that would limit the damage caused by federal mismanagement of protected species while empowering state and local officials to pursue sensible conservation plans with their communities.”

“I am grateful to join my colleagues in introducing the Native Species Protection Act, which empowers states to manage wildlife populations unique to their state,” said Hatch. “Time and again, we have witnessed federal mismanagement of numerous species, especially in my home state of Utah. In my view, state officials—not Beltway bureaucrats—are best equipped to manage animal populations in a responsible manner, especially those populations that fall exclusively within their borders. This legislation authorizes state wildlife management authorities, in cooperation with local communities, to develop balanced conservation plans that meet the needs of state-specific species and affected areas. I’m pleased to be a part of this effort and hope that the Senate will act quickly to pass this commonsense legislation.”

The need for ESA reform is clear, and one of its major flaws is what many consider unconstitutional overreach on private property, and the resulting unpopularity of the Act, and mistrust of government. Minor missteps which violate ESA regulations can have a devastating effect on property owners and small businesses. Although a decision by the Supreme Court on the Utah prairie dog case could settle the dispute for the time being, legislative fixes are needed to clarify jurisdiction and mitigate harmful and expensive conflicts.

[paypal_donation_button]

Free Range Report

[wp_ad_camp_3]

[wp_ad_camp_2]