In Utah’s San Juan County and nearby reservations, residents say their dissenting voices were ignored in the designation process for the area, a canyon region of red rocks named for two towering buttes called the Bears Ears. Locals are concerned about restricted access to the area, home to many sacred and cultural sites. They gather traditional herbs and nuts on the land, and some Navajo without electricity rely on it for firewood.

Erin Clark

Monumental Dissent Over Bears Ears

Here’s what some Native Americans say to well-meaning government and private conservationists trying to preserve their ancestral land: Please stop helping us so much.

Navajos in southeastern Utah living closest to the Bears Ears National Monument, a 1.35 million-acre tract set aside for preservation last year by the Obama administration, are welcoming moves to shrink it by President Trump’s interior secretary, Ryan Zinke.

That’s because many locals fear the larger designation could backfire by encouraging tourists to traipse more widely over the fragile landscape, turning a victory for Native Americans into a hollow one.

Utah Sen. Orrin Hatch said Trump called him last month to say he intends to follow through on proposals to shrink Bears Ears by hundreds of thousands of acres.

The locals’ objections reflect not only a conflict over the preservation of tribal heritage but a wider one over expanding presidential designations of public lands as national monuments – even expanses of ocean.

President Obama created or enlarged a record 34 national monuments in his time in office, according to the Washington Post — two more than the previous top designator, Franklin D. Roosevelt. The Obama designations included a 4,913-square-mile “marine national monument” off the coast of New England.

Carleton Bowekaty, who serves on a tribal panel advising on Bears Ears, defended the Obama designation, noting concerns over its size had been heeded when it was reduced from a proposed 1.9 million acres.

But critics charged that the still-vast designation, urged on Obama by environmental groups and a tribal coalition, was an abuse of presidential authority under the Antiquities Act of 1906. A hallmark of President Theodore Roosevelt’s progressivism, the law allows presidents to make monument designations of “the smallest area compatible” with protecting important sites, including restricting commercial development.

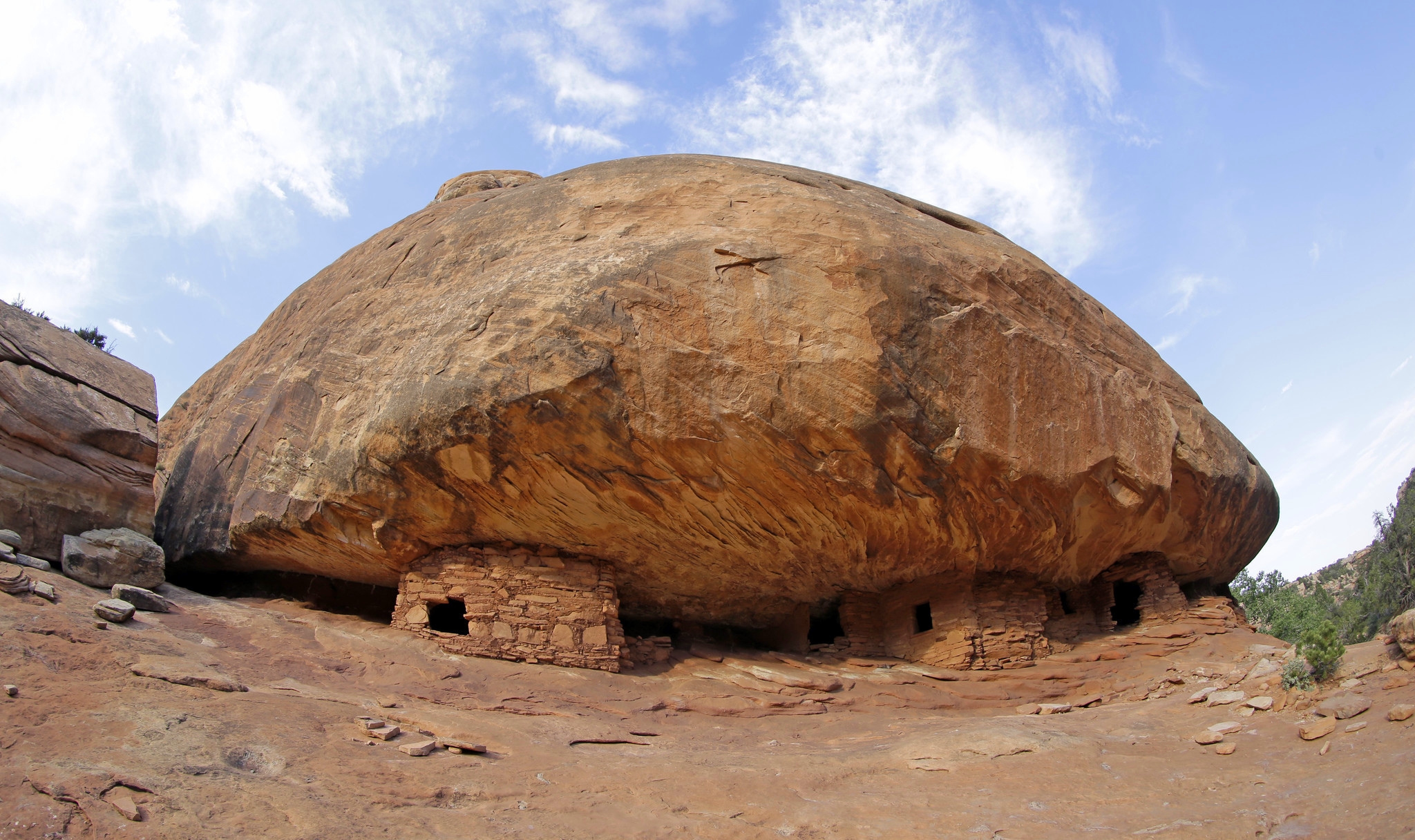

In Utah’s San Juan County and nearby reservations, residents say their dissenting voices were ignored in the designation process for the area, a canyon region of red rocks named for two towering buttes called the Bears Ears. Locals are concerned about restricted access to the area, home to many sacred and cultural sites. They gather traditional herbs and nuts on the land, and some Navajo without electricity rely on it for firewood.

Some previously opposed residents appear to have softened their stance, but others remain determined in their opposition. The designation is a “solution to a problem that didn’t exist,” said Jami Bayles, a lifelong resident of Blanding, Utah, and president of the Stewards of San Juan County, a community-elected group created to help residents elevate their voice in the monument debate.

Byron Clarke, vice president of a local Navajo community group called the Blue Mountain Diné, told the Deseret News last year that the fact that dozens of Native American groups supported the Bear Ears designation is misleading. “The more distant you are as a Navajo and tribal member the more likely you are to support the monument because you view it as an abstraction or concept or theory of tribal sovereignty,” he said.

Locals doubt assurances that the monument designation won’t restrict their access to the land, and argue that fears of future drilling and extraction are unfounded because there’s not enough oil or other resources there to make that profitable.

Ryan Benally, a Navajo resident who lives nearby, said he and other locals have been verbally attacked for opposing the monument. “They’re calling us right-wing nuts,” he said. “Here I am, a Democrat, but I don’t agree with the monument. Here I am, now an extremist for not supporting an un-funded monument.”

Bears Ears was the ancestral home of many southwestern tribes, including Utah’s native nations, the Ute, Paiute, and the Navajo. Today, the closest reservations to Bears Ears are those of the White Mesa Utes and of the Aneth Navajo, the only Navajo chapter that did not officially support making Bears Ears a monument.

Obama officially designated the monument on December 28, 2016, after a protracted campaign by the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition and environmentalist allies.

The coalition brought together five southwestern tribes – the Navajo Nation, Hopi Nation, Zuni Tribe, Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, and the Ute Indian Tribe of Uintah Ouray. Anti-monument skeptics suggest that the coalition was nudged into being by the environmental groups rather that arising organically from a common purpose.

Supporters and detractors remain split over whether the monument designation is a necessary step in the battle against the looting of Bears Ears archaeological sites.

The tribal coalition says it is. Benally and Bayles disagree, although they concede looting is a concern. The FBI’s 2009 Operation Cerberus Action raids of nearby homes turned up over 400,000 native artifacts, from ceramic bowls to ceremonial headdresses to arrows.

[paypal_donation_button]

Free Range Report

[wp_ad_camp_3]

[wp_ad_camp_2]