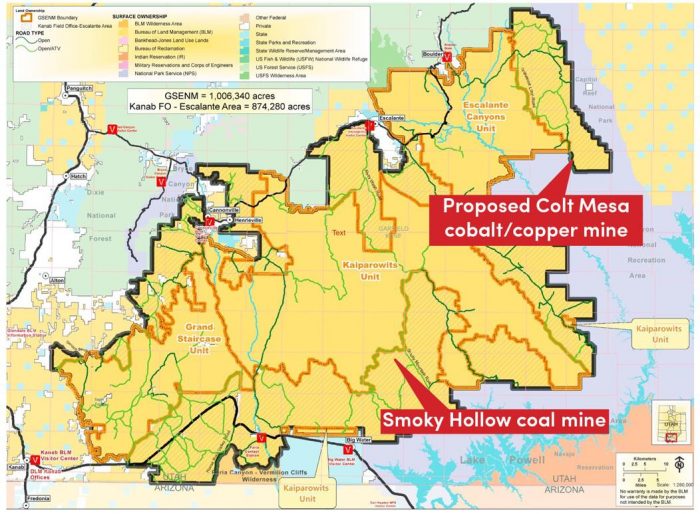

As consumers, we have an absolute moral and possibly a national security imperative to explore alternatives to cobalt dug up overseas under conditions of unimaginable horror and embedded in our lifestyle…One alternative could be the proposed subsurface Colt Mesa cobalt and copper mine 30 miles or so east of Boulder, Utah, just outside the current boundary of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in southern Utah.

Bill Keshlear

The Grand Staircase Story: morality of mining, no-compromise environmentalists, unreliable sources…

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

William Shakespeare, Macbeth, Act 5, Scene 5

Convenience of modern life comes with environmental trade-offs, inconvenient truths.

This report was researched and written using a Mac Book Pro whose power was stored in a lithium-ion rechargeable battery that needs cobalt. The original power stored in the battery was likely generated by coal dug up by miners in eastern Utah and transported to a power plant using trains and trucks powered by diesel fuel refined after being pumped up from fields also located in eastern Utah.

Consumers in the United States, like myself, use the majority of the world’s cobalt. Prices for it on the world market reflect our skyrocketing demand. But there’s a darker cost: a history of human-rights violations, including use of child labor associated with production of 66 percent of the world’s supply in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

As consumers, we have an absolute moral and possibly a national security imperative to explore alternatives to cobalt dug up overseas under conditions of unimaginable horror and embedded in our lifestyle. (The Department of Homeland Security considered one cobalt mine in the Congo so vital that its “incapacitation or destruction … would have a debilitating impact” on U.S. security or the national economy.)

One alternative could be the proposed subsurface Colt Mesa cobalt and copper mine 30 miles or so east of Boulder, Utah, just outside the current boundary of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in southern Utah.

Yet even the remote possibility of its becoming a reality has unleashed a backlash of NIMBYism (“not in my backyard”). The refrain goes something like this: “We like our cell phones. Electric cars can power a clean transportation future. Just don’t go digging holes in our desert preserve for the stuff that makes ’em work. Dig for cobalt someplace else.”

Currently, the only “someplace else” in the United States is about 500 miles north at a mine poised to begin operations in the Idaho Cobalt Belt.

Unlike their Utah counterparts, members of the Idaho Conservation League out of Boise don’t seem to mind it their backyard. Or, they’ve at least been willing to work with miners to ensure operations near Salmon and processing facilities in Blackfoot are clean and safe.

An agreement between the Idaho environmentalists and Canada-based eCobalt established a conservation fund for projects near the mine, and they’ll be monitoring eCobalt to ensure it abides by environmental regulations. The company says it’s committed to the ethical demands of global giants such as Tesla and Apple, which is considering the Idaho cobalt as a source that guarantees its products aren’t connected to atrocities.

However, Glacier Lake Resources, which has staked a claim to the long-abandoned mine down in Utah, faces problems that might discourage investors, according to Tim Peterson at the environmental nonprofit Grand Canyon Trust, and render the whole thing moot. First, there’s simply not much water. Then, there’s an absence of heavy-duty haul roads, electricity and access to rail lines. It’s a long, long way from anywhere the ore could be processed.

What’s more, Panasonic, supplier of Tesla batteries, announced in May that it’s developing a battery that doesn’t need cobalt. Demand for the morally dirty mineral is elastic. While currently increasing and expected to exceed supply within the next few years, demand might plummet if viable alternatives can be developed.

President Donald Trump’s proclamation last year shrunk the monument to a little over half of its original size and placed the mine outside its boundary. Environmentalists considered it a bald-faced attack on the foundations that helped create the National Park system, the Antiquities Act, and they’re pulling out all the stops to reverse it.

Why would any investor pump tens of thousands into preliminary phases of a project that could go belly up because of an adverse ruling in federal court?

(Litigation could be politically useful for environmentalists, possibly delaying full implementation of the proclamation until the president leaves office and a more sympathetic administration takes over. Alternatively, the Bureau of Land Management has fast-tracked the normally lengthy process of writing a plan to guide monument land use. Have agency managers been directed to speed things up to ensure Trump’s version survives his rocky tenure? Once done, this stuff is difficult to undo.)

Potential Colt Mesa investors likely understand the risks.

It’s just not a serious proposal, according to Drew Parkin, an economic development consultant for Garfield County and former field station manager for the monument. “I am going to say that I’m 95 percent confident that what you’re hearing now are basically scare tactics.” Much of the monument lies within Garfield County.

Free Range Report

Thank you for reading our latest report, but before you go…

Our loyalty is to the truth and to YOU, our readers!

We respect your reading experience, and have refrained from putting up a paywall and obnoxious advertisements, which means that we get by on small donations from people like you. We’re not asking for much, but any amount that you can give goes a long way to securing a better future for the people who make America great.

[paypal_donation_button]

For as little as $1 you can support Free Range Report, and it takes only a moment.