The government’s claim that it, and hence the public, had a right to use the property without purchasing or negotiating with the family for an easement, meant that Wonder Ranch had to file a lawsuit against the government to quiet title to the property—meaning eliminate the government’s claim to a prescriptive easement.

Terry Anderson

Property and Environment Research Center

USFS Claims Easement through Cooperative Landowner’s Front Yard

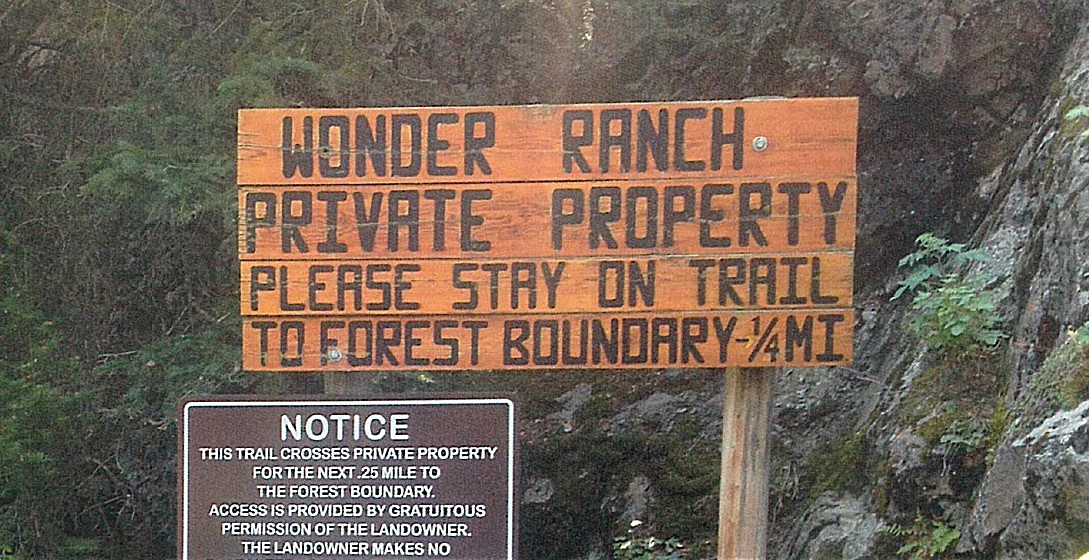

After years of hearing from my friend Frank-Paul about the beauties of Indian Creek in the Madison Range, south of Ennis, Mont., my wife and I saddled our horses at the designated U.S. Forest Service trailhead more than a mile from the Lee Metcalf Wilderness Area boundary. For the first mile or so, signs along the trail said, Private Property. Please Stay on the Trail. Then we came to an open gate with a similar sign, but with the added invitation saying, Access is provided by gratuitous permission of the landowner.

Because Indian Creek has carved a narrow canyon, the trail passes through the middle of an 80-acre parcel known as Wonder Ranch, but we knew the owner’s policy had always been to grant everyone friendly permission, even though the trail ran about 15 yards from the owner’s front porch.

Knowing Frank-Paul for decades, I couldn’t resist yelling out, “Is Frank-Paul home? I could use a glass of water,” as a joke. Soon, his 80 year-old mother-in-law, Mrs. Hudson, stepped through the door to politely tell me Frank-Paul had gone hiking with his family. I was embarrassed to have bothered Mrs. Hudson, but she remained as friendly as she had been since purchasing the property in 1968.

Mrs. Hudson is gone today, but the family’s legacy of allowing access to the bordering public land lives on. As a letter from Madison District Ranger Blaine Tennis to Wonder Ranch, dated Nov. 22, 1960, put it: “[You] have been very cooperative in allowing us to cross your land to get to the National Forest.” More letters, over the course of 40 years, four district rangers and even the forest supervisor reaffirmed ranger Tennis’ statement that access across Wonder Ranch was by gratuitous permission of the landowner. Even as late as 2004, Madison District ranger Mark Petroni wrote, “No easement exists across the Wonder Ranch.”

Unfortunately, relations between the Hudson family and the USFS became more contentious as the agency began demanding an access easement. Even then the family sought a win-win solution, offering to grant such an easement in return for rerouting the trail away from their house. They even volunteered to pay for the rerouting and bridge construction. According to District Ranger Petroni (Feb. 10, 2006), “They [the Hudsons] have offered to partner with us to acquire an easement across their property, assist with acquisition of an easement across their neighbor the CB Ranch and help fund NEPA [environmental review] and construction of a new trail location that avoids their lawn. This potential partnership is too good to pass up.”

But the USFS did pass it up, instead filing a statement of interest in the Hudson property in 2011, claiming that “The United States of America states that it has and claims an easement for the Indian Creek trail 328 over and across [Wonder Ranch].” It claimed that continuous, adverse use of the trail created a prescriptive easement for public use of the trail without permission of the landowner (adverse meaning: occupation of land to which another person has title with the intention of possessing it as one’s own).

The government’s claim that it, and hence the public, had a right to use the property without purchasing or negotiating with the family for an easement, meant that Wonder Ranch had to file a lawsuit against the government to quiet title to the property—meaning eliminate the government’s claim to a prescriptive easement.

Substantiating a prescriptive easement requires evidence of open, notorious, exclusive, adverse, continuous and uninterrupted use without that use being granted by permission of the landowner. But Wonder Ranch had continuously granted gratuitous permission, as stated on their sign (see top left) and acknowledged by the USFS for more than 50 years. Moreover, in the court proceedings the government could not provide a single witness testifying to continuous and uninterrupted use as claimed by the USFS. It could only document 30 users per year, as evidenced by the National Forest Trail Registers at the Indian Creek trailhead from 1969 and 1970. Nonetheless, on October 24, 2016, U.S. District Judge Sam Haddon issued his opinion in favor of the government’s claim to a prescriptive easement.

The case has significant implications for three reasons. First, of course, the decision is important to the landowners because they had to spend thousands of dollars trying to defend their property rights, and they still lost. Second, far beyond the boundaries of Wonder Ranch, the decision has implications for how the government obtains access across private property to federal lands. Third, such rulings discourage landowners from allowing public access in the first place and ultimately undermine the neighborly relations between public land users and landowners that have been the tradition in the West. The message to all landowners became clear: If you allow even a few people to cross your property, you may find yourself in court spending thousands of dollars on lawyer fees and ultimately losing your property rights.

To see how far Forest Service officials are willing to push for access across private property, consider the advice District Ranger Alex Sienkiewicz (Yellowstone Ranger District) posted on July 7, 2016, on the Facebook page of the Public Land/Water Access Association, a group notorious for advocating public access as an entitlement. Sienkiewicz’s advice: “NEVER ask permission to access the National Forest Service through a traditional route shown on our maps EVEN if that route crosses private land. NEVER ASK PERMISSION; NEVER SIGN IN (concerns—come see me). … Whatever past DRs [district rangers] or colleagues have said, I am making it clear, DO NOT ASK permission and DO NOT ADVISE publics to ask permission… By asking permission, one undermines public access rights and plays into their lawyers’ trap of establishing a history of permissive access.”

There are many places across Montana and the west where access to public land requires crossing private land. With the Wonder Ranch ruling and the advice from the Yellowstone District Ranger, each represents another potential lawsuit. Consider a popular traditional route south of Bozeman shown on USFS maps (names omitted to protect neighborliness). This trail can be accessed from two points, one a designated trailhead with a well-established easement and one that requires crossing private land without an easement where the sign at the gate says, access is for subdivision residents only. Since the subdivision was created in the early 1970s, residents and a handful of other people have enjoyed permissive access, understanding that the landowner is welcoming them with permission. Seldom does the landowner acknowledge that people are crossing the private property or explicitly grant permission.

Now suppose the USFS claims a prescriptive easement as in the Wonder Ranch case. Does access since the 1970s create a prescriptive easement? With the Indian Creek case as precedent and the admonition of the district ranger, it would appear the answer is yes. Come one, come all. To landowners who want to maintain some control of their property, the message is lock the gate rather than be neighborly.

There is an alternative approach to access, which the USFS used in the Bridger Mountains where a landowner locked a gate across a road leading to public land. In the Bridgers, rather than fight an expensive court battle claiming a prescriptive easement, the USFS simply rerouted the road around the private property. Yes, building the new road will cost taxpayer dollars, but legal battles are costly too.

In a Nov. 29, 2016, editorial the Bozeman Chronicle called the common-sense approach of the Bridger Mountains example a “slippery slope” because, if the Forest Service “caves” and opts to negotiate instead of litigate, it might set precedent in future disputes where private landowners claim “agencies have other options than crossing their land.”

Another example in the Mill Creek drainage south of Livingston also shows that the USFS can use common sense. The Mill Creek landowner is willing to exchange more than 400 acres of private land for a “sliver” of public land on which a previous owner had mistakenly built a barn decades ago. Quoted in the Chronicle, Ed Bazinet, the landowner, called the barn “part of the character of the ranch.” The deal is not complete, however, because the USFS insists he pay $9,000 for the sliver in addition to donating hundreds of acres to the public. To that Mr. Bazinet appropriately says, “It doesn’t make sense to me.” Interestingly, District Ranger Sienkiewicz, who advocates “DO NOT ASK permission,” is working to get non-profit groups, such as Trout Unlimited, to put up some of the funds to complete the win-win exchange.

The lesson to be learned from these examples is that litigation penalizes both private landowners and the public when it crowds out cooperation as the solution for public access disputes. Just as the Hudsons welcomed people with signs granting permission, other landowners have kept their gates opened in return for respect of private property rights from public users. For years, a ranch bordering public land in the Crazy Mountains asked people to sign in, record their destination, and suggest a departure date before granting permission. Now that ranch is targeted as one for which Ranger Sienkiewicz says the public should not ask permission for access.

In yet another example, a landowner south of Livingston worked with the Southwest Montana Climbers Coalition to designate a route through their land (which is directly between a public road and a popular rock climbing area on BLM property known as Allenspur). The route is operated through good faith between the climbing community and the landowner, but the question is what will happen to this good faith if landowners feel they will end up in court defending their property rights against a prescriptive easement? And what will happen if access groups no longer are required to negotiate good-faith agreements with landowners and instead simply claim a public right to access?

If access becomes “the biggest resource issue of the 21st century,” as the Bozeman Chronicle recently claimed, it will be because the public, through its land management agencies, demands access without cooperation and negotiation. For many years the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks admonished people to “always ask permission to hunt and fish on private land.” The fact that this admonition is no longer prominently displayed on FWP publications also suggests a shift in how we think about access. By shifting from asking permission to claiming entitlement, we tear at the social fabric of cooperation among landowners, federal and state agencies, and public land users that has been the tradition in Montana.

That day when I rode through Wonder Ranch, I remember feeling badly for disturbing Mrs. Hudson. I didn’t feel entitled to ride through her front yard any more than I would think someone is entitled to picnic on my deck. I felt that I was lucky the Hudson’s were preserving their little piece of Montana’s nature that we all cherish. We should all thank such neighbors.

Editor’s Note: At the editor’s invitation, a US Forest Service spokesperson offered the following comment: “It is a good thing that the issue of public lands access is receiving public attention. Access is a critical part of providing everyone the ability to enjoy their public lands. The agency believes strongly that working together toward common solutions is the best approach. However, there will also be disagreements about rights of access. The Forest Service respects private property rights and are obligated to defend public rights of access. More and more, people are faced with barriers, locked gates and no trespassing signs on routes that have been historically used to access public lands. Some of these historic routes have perfected/recorded easements while others remain unperfected and occasionally become a matter of dispute. For historic routes where access is in dispute and the Forest Service requests permission or signs in, public access rights on that road or trail can be undermined. The agency has to be thoughtful about actions that may hinder the public’s rights in the eyes of the court should these access issues result in litigation.” —Marna Daley, Public Affairs Officer, Custer Gallatin National Forest Service

This article originally appeared in The Montana Pioneer on February 6, 2017.

Terry Anderson is the William A. Dunn Distinguished Senior Fellow and former President and Executive Director of PERC as well as the John and Jean De Nault Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University. He believes that market approaches can be both economically sound and environmentally sensitive.

Free Range Report