New information that’s emerged about threats to the fish and their critical habitat doesn’t rise to the level of requiring additional environmental analysis of grazing, Clarke said.

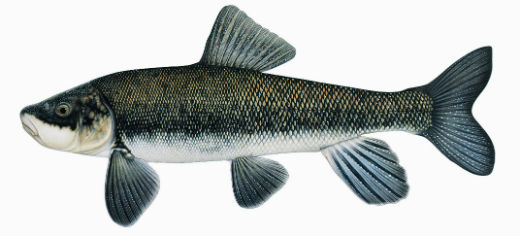

For example, although the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has reached the “alarming” conclusion that shortnose suckers face a “high degree of threat of extinction,” this finding doesn’t influence the Forest Service’s assessment of grazing, he said.

Mateusz Perkowski

Judge dismisses lawsuit against grazing on eight Oregon allotments

A federal judge has rejected environmentalist arguments that cattle grazing has unlawfully harmed endangered sucker fish in Oregon’s Fremont-Winema National Forest.

U.S. Magistrate Judge Mark Clarke has thrown out a lawsuit by three environmental groups — Oregon Wild, Friends of Living Oregon Waters and the Western Watersheds Project — which claimed that grazing was unlawfully authorized on eight allotments in the Lost River watershed.

The plaintiffs accused the U.S. Forest Service of “ignoring widespread evidence of riparian problems” that adversely affected the Lost River sucker and shortnose sucker, which are federally protected under the Endangered Species Act.

However, the judge has ruled that plaintiffs failed to prove that grazing degraded streams in violation of the National Forest Management Act.

Conditions have improved in many riparians areas despite continued grazing while recovery trends are “not significantly different” among sites that are grazed and those that are not, Clarke said.

“This would tend to indicate grazing is not the reason for any failure to attain (riparian management objectives) in streams found on the challenged allotments,” he said.

While the environmental groups have pointed to evidence of deterioration along portions of some creeks, they haven’t shown “watershed level” and “landscape-scale” failures to live up to fish-recovery objectives, Clarke said.

The “creek-specific observations” by environmental groups aren’t enough to “successfully rebut” the Forest Service’s interpretation of the data, he said.

“Finally, many of the creek assessments plaintiffs point to as evidence of a failure to attain (riparian management objectives) actually show improving or stable trends,” the judge said.

The Forest Service’s decision to authorize grazing on the eight allotments was based on “reasonably gathered and evaluated data” related to fish recovery strategies mandated under the National Forest Management Act, he said.

The judge’s decision reinforces the idea that the Forest Service must strive toward the goals set by the inland fish strategy for national forests, rather than meet those standards instantaneously, said Scott Horngren, an attorney with the Western Resources Legal Center who represented ranchers who intervened in the case.

“You need to look at it for the whole watershed, not just a hundred feet of stream,” Horngren said.

Clarke also dismissed the plaintiffs’ Endangered Species Act arguments, ruling they were moot because future grazing approvals will rely on a new consultation among federal agencies on the two fish species.

Horngren said the federal government is working on that consultation, which his clients hope will be finished in time for the 2017 grazing season.

It’s possible that new litigation will ensue over that consultation when it’s complete, he said.

Capital Press was unable to reach attorneys for the environmental groups as of press time.

The environmental groups’ claims of National Environmental Policy Act violations were likewise dismissed because the plaintiffs hadn’t fully “exhausted” administrative challenges against the grazing plans, the ruling said.

New information that’s emerged about threats to the fish and their critical habitat doesn’t rise to the level of requiring additional environmental analysis of grazing, Clarke said.

For example, although the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has reached the “alarming” conclusion that shortnose suckers face a “high degree of threat of extinction,” this finding doesn’t influence the Forest Service’s assessment of grazing, he said.

“While FWS concluded that significant threats to shortnose suckers’ viability remain and thus that their chance of extinction is high, it did not identify grazing as one of those threats; in fact, it made no mention of grazing at all,” the judge said.