Regardless of whether or not the new boundaries are fair, the process to create the boundaries was completely controlled by the judicial branch of government and the final decision was made by the federal judge.

DUST IN THE WIND

by Bill Boyle, Editor

As originally published by San Juan Record

Does Supreme Court decision have local implications?

The United States Supreme Court issued a ruling in the past week regarding political gerrymandering.

In brief, the court ruled that the judicial system should not be the entity that draws the boundaries of political subdivisions.

The majority opinion is that the Constitution set up a process in which the legislative branch of government makes the voting boundary decisions and the judicial branch should not interfere.

This issue is of intense interest in San Juan County with the current controversies regarding voting boundaries in the county and a ruling on a pending appeal expected any day by the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals.

In 2017, new voting boundaries were created by Federal Judge Robert Shelby as the culmination of a multiyear voting rights lawsuit between the Navajo Nation and San Juan County. Shelby’s ruling was appealed by San Juan County to the Tenth Circuit.

I asked several attorneys who are involved in the local case about their views of the new Supreme Court ruling.

In general, they state that the Supreme Court ruling may not directly impact that local situation since the Supreme Court ruling was regarding political gerrymandering.

The local case regards racial gerrymandering.

However, I feel that the core of the Supreme Court ruling may be very applicable to the local case. The concern I have is how the current voting boundaries were drawn and ultimately, by whom they were approved.

In 2017, Judge Shelby hired a special master to draw the new voting district boundaries. Dr. Bernard Grofman, from Irvine, CA, has a host of impressive credentials and may have done a credible job creating voting boundaries. He was paid $75,000 for his work.

Who knows, in a different time and place, he may have been a great central planner.

Dr. Grofman drew the boundaries, and two quickly-called meetings were held to receive input from the public. These meetings cannot be called public meetings since they did not meet the notification requirements for actual public meetings in Utah.

A few minor adjustments were made and Judge Shelby announced the results. It may have been because of the pending elections, but the decision seemed rushed and forced.

Regardless of whether or not the new boundaries are fair, the process to create the boundaries was completely controlled by the judicial branch of government and the final decision was made by the federal judge.

There are winners and losers as a result of the decision. The new boundaries have set up a new reality in San Juan County, with a Native American majority on the Commission.

It also effectively disenfranchised the largest community in the county, with the Blanding area split between the three commission districts.

There has been significant misunderstanding of the process that resulted in the previous voting districts in 1984.

I recently reviewed the 1984 issues of the San Juan Record to better understand the issue. I walked away from the process with an increased appreciation for what happened in 1984. I also had a growing concern about what happened in San Juan County in 2017.

In 1984, the process to create the voting districts, at several key points along the way, was a public process. This is in marked contrast to the process to create the current voting districts.

This may be due, in part, to the fact that the 1984 legal action was filed by the U.S. Department of Justice. While San Juan County officials vigorously defended their position, they also seemed eager to find a workable solution with their counterparts in the federal government.

The current action was initiated through a lawsuit filed by the Navajo Nation and others against San Juan County.

This immediately set up a confrontational relationship between the two parties which only seemed to grow over time. The relationship between Commissioners and Leonard Gorman, of the Navajo Nation Human Rights Commission, was particularly confrontational.

As a result, there was little cooperation between the two parties in the current action. In contrast, the cooperation between competing entities in 1984 was impressive.

The process toward change in 1984 was driven by the San Juan County Commission, but included a host of organizations, including the Navajo Nation and other tribal officials, attorneys from the Office of Civil Rights, the general public, and other key organizations.

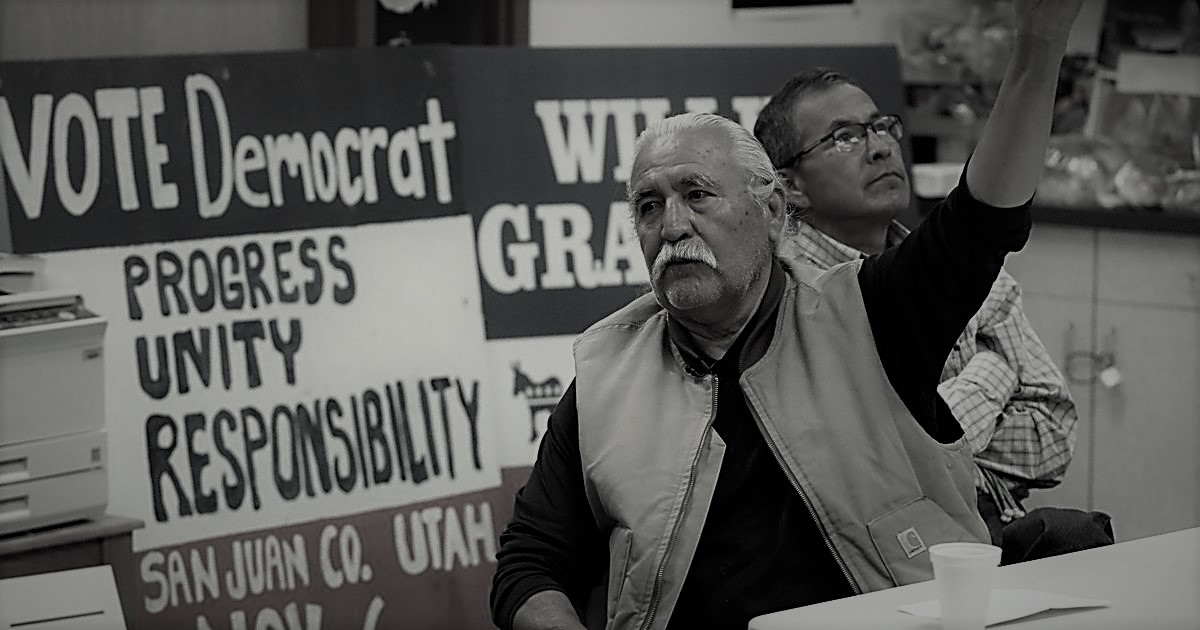

The Utah Navajo Development Council (UNDC), in particular, played an important role in the process. The Chairman of the UNDC board, Willie Grayeyes, was very involved in the entire process.

In total, 13 separate voting district maps were considered before a final option was selected and presented to voters. The process was open and accessible to all.

Most importantly – to me at least – is the fact that voters had a chance to make their preference known at the ballot.

In August, 1984, voters approved the concept of voting districts for the Commission seats. This concept was accepted by 60 percent of the voters of San Juan County, with the majority of voters favoring the voting districts in 16 of the 20 precincts.

The creation of voting districts was a key aspect of the solution sought by the Office of Civil Rights.

Several months later, in the November 1984 general election, voters approved the boundaries of the new districts. These voter-approved boundaries remained the same for nearly 30 years.

In the general election, 64 percent of voters approved the new voting districts, with 2,055 approving and 1,161 opposing.

Precincts on the reservation approved the plan by a 20 percent margin and non-reservation areas supported the plan by a 30 percent margin. Only the Navajo Mountain precinct opposed the plan.

It is remarkable that voters in 19 of the 20 precincts approved a plan that was, by its very nature, so divisive. Voters reached a consensus on a very difficult issue.

The process in 2017 has resulted in an incredibly divided county.

Regardless of how one feels about the outcome, the process in 1984 was democratic and open. It involved compromise and required listening to all sides. It is the essence of the American government that voters were able to approve the plan.

In contrast, the most recent changes were simply imposed by the wrong branch of government.

The most recent Supreme Court ruling suggests that following that process is not optimal to a democracy.

See more from the San Juan Record here

Free Range Report

Thank you for reading our latest report, but before you go…

Our loyalty is to the truth and to YOU, our readers!

We respect your reading experience, and have refrained from putting up a paywall and obnoxious advertisements, which means that we get by on small donations from people like you. We’re not asking for much, but any amount that you can give goes a long way to securing a better future for the people who make America great.

[paypal_donation_button]

For as little as $1 you can support Free Range Report, and it takes only a moment.