A 13-page memorandum to the Budget Committee this year contains his case for the proposed “paradigm shift” as well as calling for $50 million to facilitate conveyances of federal land to state, local and tribal governments.

Bartholomew D. Sullivan

Republicans making progress on longtime goal for more local control of federal lands

WASHINGTON — As the new Republican-dominated House convened in early January, anticipating the arrival of President Trump, the chairman of the House Natural Resources Committee declared it time for a “paradigm shift” in how the more than 25% of the country that is owned by the federal government is managed.

Almost eight months into an all-Republican-led effort, it’s clear that shift is under way.

It started almost immediately. On the first day of the new Congress, Republicans passed a rule that made it easier to make conveyances of federal land by treating such transfers as cost-free even if they would potentially cause losses of revenue from mining or drilling rights.

Days after Trump took office, then-congressman Jason Chaffetz of Utah introduced legislation to dispose of 3.3 million acres of public land in 10 Western states. After irate calls and protests, he withdrew the bill days later.

In March, the new Interior secretary, Ryan Zinke, repealed a January 2016 moratorium on new coal leases on federal land by the Bureau of Land Management before a planned three-year environmental assessment — that would have looked into “the social cost of carbon” — could be completed.

In April, the president asked Zinke to study the size of national monuments made since 1996 by presidential fiat under the Antiquities Act. The review was in the context of a new policy of “energy dominance” and the planned acceleration of resource extraction from public lands.

In June, Zinke, a former Montana congressman and Navy Seal, said the department would postpone elements of the methane rule that requires energy companies to capture the natural gas on public lands rather than flaring it off, the standard industry practice.

In a mid-July meeting with Office of Management and Budget Director Mick Mulvaney, Zinke said he planned to implement the energy dominance Trump has called for by requiring his department to reach faster decisions on leases and permits on federal land, and becoming a partner with extraction industries rather than an adversary. Mulvaney said Interior was “leading the way” in the kinds of deregulation Trump advocates.

Zinke’s views on the evolving Republican House public lands strategy are complicated. He says he wants to be a good steward and opposes turning over federal land to local or state governments or private interests. His justification for delaying full implementation of the methane rule wasn’t so much that it is bad public policy, since it would stop wasting a public resource that could generate revenue, but balancing that goal with the cost to the industry.

While raising revenue from public lands seems in tune with the goals of House Republicans such as Natural Resources Chairman Rob Bishop of Utah, Zinke is not entirely on board with all their agenda. When Republicans convened their national convention in Cleveland last summer, the platform committee agreed to a policy of providing “an orderly mechanism requiring the federal government to convey certain federally controlled lands to the states.” Zinke, a member of the committee who disagreed with the policy statement, walked out.

Zinke told senators at his confirmation hearing, and in several public appearances since, that one of his heroes is Theodore Roosevelt, the Republican president who doubled the number of national parks and signed the 1906 Antiquities Act. At a White House roundtable with reporters in July, Zinke talked of lessons learned from John Wesley Powell, who surveyed the West with the U.S. Geological Survey in the late 1890s, and Gifford Pinchot, the first chief of the U.S. Forest Service from 1905 to 1910.

It’s clear that this Interior secretary, comfortable making the rounds in wrinkled jeans and a cowboy hat, is steeped in the history of his department but also devoted to the mission to make the country’s natural resources pay. Unlike Ronald Reagan’s lightning rod of an Interior secretary, James G. Watt, who resigned after two years in 1983 following showdowns with Congress over coal mining and offshore oil drilling, Zinke appears to favor diplomacy.

As Zinke travels the country looking at national monuments and parks, back in the massive C Street Interior Department Udall Building headquarters, his pinstriped deputy, sworn in Aug. 1, is David L. Bernhardt. Bernhardt is an oil and gas lobbyist and lawyer whose clients have included Halliburton Energy Services, the company once run by former vice president Dick Cheney; Rosemont Copper Co., which is seeking a permit to mine in Arizona; and Cadiz Inc., which is seeking access to the aquifer water under the Mojave Desert, according to the environmental activist group Greenpeace’s “Polluter Watch” project.

Also on staff is associate deputy secretary James Cason, who notified several members of the senior executive staff in June that they were being reassigned. One, director of policy analysis Joel Clement, the department’s specialist on arctic climate change, was reassigned to an office handling oil lease royalty payments. He wrote a Washington Post op-ed saying he was being retaliated against and that the transfer was intended to make him quit. Cason held Interior jobs under George W. Bush and was involved in minerals management under Ronald Reagan.

After learning of the reassignments, Sen. Maria Cantwell, D-Wash., and seven other Democratic senators wrote to the Interior Department’s inspector general, saying that the suggestion that the executives were moved to silence or “punish them for the conscientious performance of their duties is extremely troubling and calls for the closest examination.” The senators called the transfers “a serious act of mismanagement” and “an abuse of authority.”

Soon after he was named, the department’s new principal deputy solicitor, Daniel H. Jorjani, was called as a witness before Bishop’s Natural Resources Committee oversight hearing June 28 to examine the impact of “excessive litigation” filed against the department.

While the committee’s ranking Democrat, Rep. Raul Grijalva of Arizona, questioned the entire premise of the hearing, Rep. Tom McClintock, R-Calif., sought to discredit environmental activists and those implementing consent decrees by asking Jorjani what it meant for an environmental organization to “sue and settle.” The witness said it was a method of achieving a policy objective through resort to the courts.

[wp_ad_camp_1]

But McClintock, chairman of the subcommittee on federal lands that had held a June 8 hearing on “burdensome litigation” affecting the U.S. Forest Service, had a more sinister view. “So an objective would be essentially collusion between litigants and ideological zealots in the bureaucracy to achieve a foregone or fore-ordained conclusion by court order that they know they couldn’t get by regulation or by law,” he suggested. Jorjani said he would not make any assumptions about intentions or characterize parties as zealots.

In his written testimony, Jorjani said settlements can be “useful and beneficial” by saving taxpayer money and are reviewed by federal judges to assure they’re entered into in the public interest.

“Judges are already empowered to deal with litigation that is without merit or frivolous, including the authority to punish attorneys for pursuing abusive litigation,” said Grijalva, the top Democrat on the committee. “The number of cases where courts use that authority is small, and it happens no more often with environmental litigation than in other kinds of cases.”

Later in the same hearing, witness Lois Schiffer, a former general counsel to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, clearly offended at the attacks on the integrity of civil servants, volunteered that in her experience government lawyers take their ethical obligations seriously and “do not collude.”

That got the attention of Rep. Paul Gosar. R-Ariz., who said a “blanket statement that government lawyers don’t collude is a false statement because they’re humans” and said Schiffer’s assertion was “just flabbergasting.”

Attacks on environmental plaintiffs and their attorneys’ fees has been a decades-long crusade. Bishop has championed Western land use issues since he was a state legislator in the early 1990s before bringing his cause to Washington. In May, Bishop’s committee looked at what it called “executive branch overreach of the Antiquities Act” to make the case for more local approval before designations are made. A 13-page memorandum to the Budget Committee this year contains his case for the proposed “paradigm shift” as well as calling for $50 million to facilitate conveyances of federal land to state, local and tribal governments.

Besides diminishing the size of national monuments, Bishop opposes acquiring additional lands until those it manages are put in order. Interior oversees the national parks which have $12 billion in deferred maintenance.

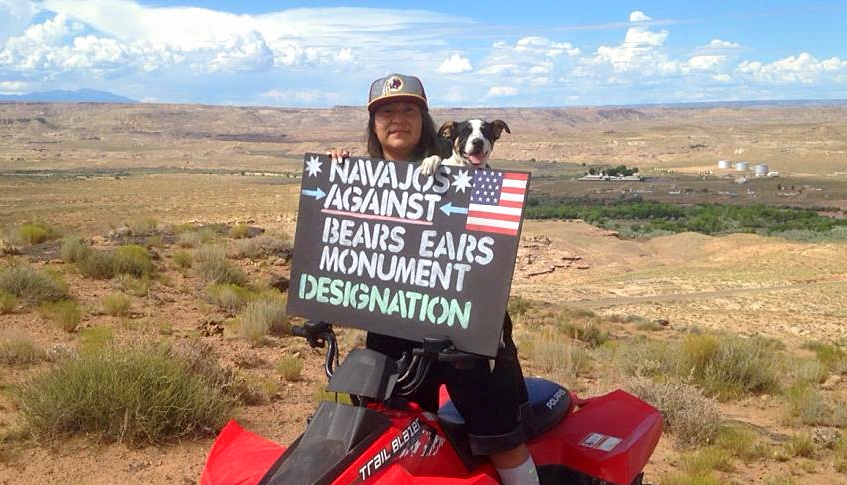

The entire Utah congressional delegation, including Bishop, objected when President Obama declared the Bears Ears national monument in December, weeks before leaving office. Its 1.35 million acres in what was Chaffetz’s district are on the list of the monuments Trump has asked to have re-evaluated, and Zinke toured it in May on horseback. He later said it needs to be scaled back to conform with the Antiquities Act provision that the area protected be the smallest compatible with that goal. A final recommendation to Trump is due later this month.

Free Range Report

[wp_ad_camp_3]

[wp_ad_camp_2]