Overall, 4.8 million acres would be closed off to mining in the Eastern Interior under the new plans, while 1.7 million would be potentially open to it. However, crucially, the proposed mining restrictions would have to be approved by the secretary of the interior, and also appear to be subject to congressional approval.

President-elect Donald Trump’s inauguration may be nearing, but that doesn’t mean President Obama’s Interior Department is finished making decisions about the future of the United States’ vast natural resources and open spaces.

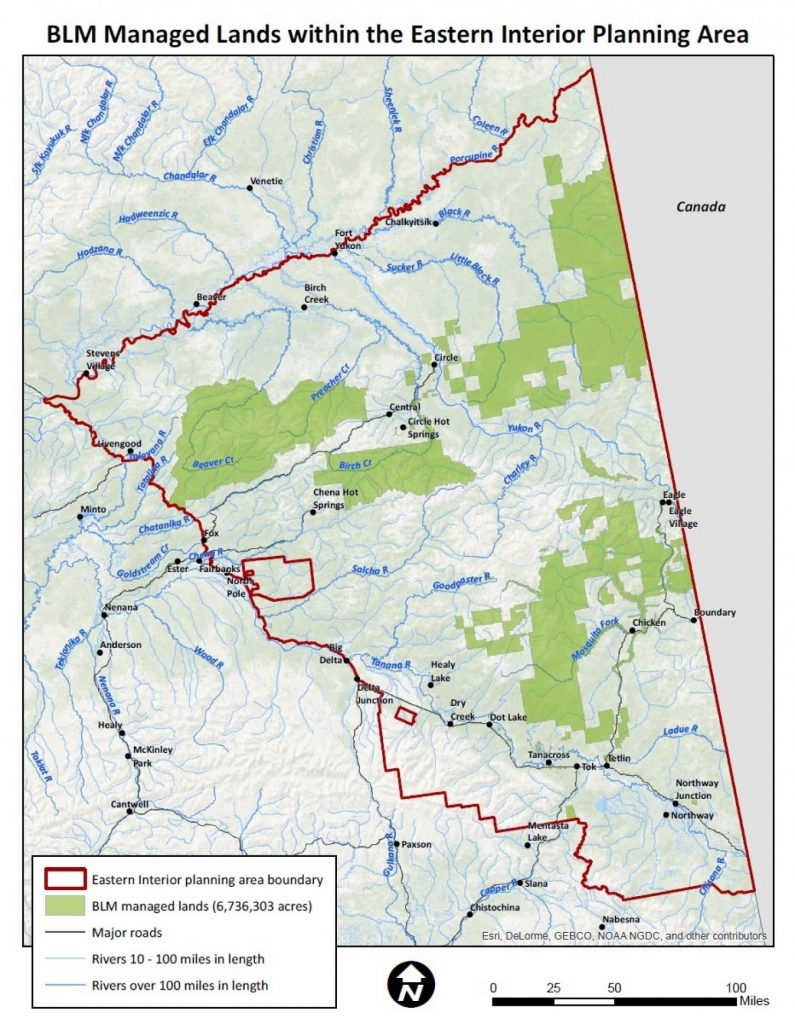

This week, the agency’s Bureau of Land Management issued four plans to shape the management of some 6.5 million publicly owned acres of Alaska’s eastern interior, a remote area stretching from Fairbanks to the Canada border that is filled with rivers, streams, forests, and very few major roads. Featuring key sections and tributaries of the Yukon river, it’s more home to animals like grizzly bears, moose, and caribou than to humans, but is also the province of native Americans including the Gwich’in, and substantial gold-mining interests in the Fortymile areanear the Canada border.

The move is just one of many Obama era conservation moves in Alaska, including designating large parts of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge as wilderness. However, it is not clear whether some of the plans’ more contentions measures — involving lands available for mining — will stay in place, due to the presidential transition just weeks away and specific laws that govern land in the state of Alaska.

Most notable in the new plans, perhaps, is the new Draanjik Planning Area, which has never before been managed by the BLM and consists of 2,360,000 acres — the largest of the four areas whose management was decided on this week. The plans propose that 77 percent of that area be shut off to mining and key areas protected for salmon, bald eagles, and native plants. (Draanjik is the Gwich’in name for what was previously called the Upper Black River, and was recently adopted by the U.S. Board of Geographic Names as the official name of the river.)

The plans collectively identify over a million acres of Alaska’s eastern interior as areas of critical environmental concern, meaning that “special management attention is needed to protect, and prevent irreparable damage to important historical, cultural, and scenic values, fish, or wildlife resources or other natural systems or processes.” This does not guarantee protection, but does signal how the lands will be managed to protect species like caribou and Dall sheep. The plans would also allow off-road vehicle use, with some “site-specific guidelines,” in the areas, and increase outdoor recreation opportunities.

“This really is the umbrella guidance document for how we make the on-the-ground decisions in the planning area for the next 15 to 20 years,” said Serena Sweet, planning and National Environmental Policy Act lead for BLM Alaska.

In addition to the Draanjik area, there are three other designated areas now receiving new operating plans. The 1,020,000-acre White Mountains Planning Area was, until now, operating under a plan completed in 1986; the 1,267,000-acre Steese Planning Area was in the same situation; and the 1,867,000-acre Fortymile Planning Area was operating under a plan dating all the way back to 1980, when Ronald Reagan was elected.

Here’s the total area of Alaska’s eastern interior region, with the publicly managed acres in green:

The plans would maintain extensive pre-existing restrictions on mining in the Steese and White Mountain areas. In the Fortymile area, near Chicken, just 40 percent would off limits. This is one of the most contentious decisions, as mining interests have objected strongly to the creation of areas of critical environmental concern in the mining-heavy area near the Canadian border.

Overall, 4.8 million acres would be closed off to mining in the Eastern Interior under the new plans, while 1.7 million would be potentially open to it. However, crucially, the proposed mining restrictions would have to be approved by the secretary of the interior, and also appear to be subject to congressional approval.

The new designation “really strikes a balance between development, conservation measures to protect traditional land, and then safeguarding habitat for important fish and wildlife,” said Suzanne Little, an officer at the Pew Charitable Trusts based in Anchorage.

“There is a lot of land identified as socioecologically important and therefore will be managed that way…but there is also a substantial amount of land being opened for resource development,” added Jamie Trammell, a professor of environmental studies at the University of Alaska Anchorage.

Nonetheless, the planning process for the Eastern Interior was quite controversial, drawing complaints from the state of Alaska and the Alaska Miners Association when the Bureau of Land Management released earlier versions of what would ultimately become its final decisions of record. Lisa Murkowski, one of the state’s senators, strongly critiqued an earlier version of the BLM’s proposal, accusing the agency of “clearly attempting to restrict economic opportunity in our eastern Interior region.”

But the agency has generally stayed the course between the proposed nearly 1,800-page plan and the final versions, saying there have been only “minor modifications, clarifications, and corrections.”

The plans are not permanent — plans are generally revised and updated every 20 years, though in this case the process has dragged to 30 or more — but they do lay down a significant marker and shape the agency’s entire strategy for these vast areas. The planning process for Alaska’s eastern interior has gone on for nearly the entirety of the Obama administration.

As far as the millions of acres that would be unavailable to mining, “that’s what the plan recommends, but it doesn’t go into effect immediately,” said Jeanie Cole, who was the project lead on the management plan for the Eastern Interior for the BLM in Alaska. The plan’s recommendations in this area “require follow-up action by the secretary of the interior.”

This is also further complicated by specific laws that apply to Alaska, including the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) of 1980, which triggers congressional involvement. So it is far from clear that the plans’ restrictions or allowances on mining will be carried out.

“The BLM recommends lifting or retaining public land withdrawals as part of the environmental review in the land use planning process. It is then at the discretion of the secretary to act upon those recommendations,” explained Lesli Ellis-Wouters, chief of communications for BLM Alaska.

And that’s only the beginning of the process. “For those acres recommended to remain withdrawn, if it is greater than 5,000 acres, it would require congressional approval” under ANILCA, Ellis-Wouters continued. “If Congress does not act on that request within a year, then the recommendation is withdrawn. For the secretary to act upon those recommendations is a lengthy process and it is highly unlikely that will take place before Jan. 20.”

Trump has nominated Rep. Ryan Zinke (R-Mont.), who has favored some increased resource development on public lands, to be the nation’s next secretary of the interior.

Still, conservationists appear pleased with the attempt to protect more of this far-flung place, and the people who live there, especially in the Draanjik area.

“It’s really unlike any other place on the planet,” said Little. “People in this region achieve over 85 percent of their food directly from the land. There are no Safeways or Piggly-Wigglys out here.”

Chris Mooney

Comments

Comments are closed.