His department’s job of policing the protesters — the vast majority who’ve been camping on federal land that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers says it will close in December for safety concerns — has cost the county more than $8 million, even with help from the state Highway Patrol and officers from various states.

North Dakota Sheriff on pipeline protests: “My job is to enforce the law.”

MANDAN, N.D. (AP) — Don’t look for apologies from the North Dakota sheriff leading the response to the Dakota Access oil pipeline protests, especially for the recent — and, in some circles, controversial — action against demonstrators who he believes have become increasingly aggressive.

“We are just not going to allow people to become unlawful,” said Morton County Sheriff Kyle Kirchmeier, a veteran of the North Dakota Highway Patrol and National Guard who was elected to his first term as sheriff about two years ago. “It’s just not going to happen.”

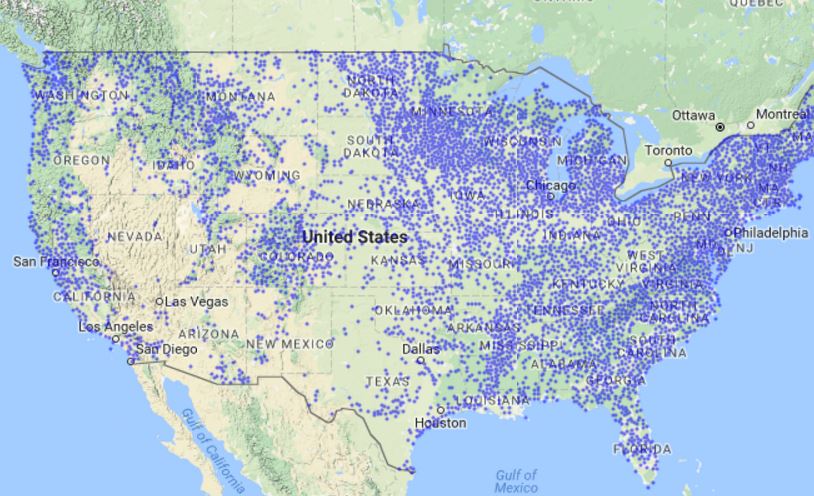

More than 525 people from across the country have been arrested during months of protests over the four-state, $3.8 billion pipeline, all here in support of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe that’s fighting the project because it believes it threatens drinking water and cultural sites on their nearby reservation.

His department’s job of policing the protesters — the vast majority who’ve been camping on federal land that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers says it will close in December for safety concerns — has cost the county more than $8 million, even with help from the state Highway Patrol and officers from various states. Their tactics, however, have drawn criticism from Standing Rock’s tribal leader as well as protest organizers and celebrities.

Standing Rock Sioux Chairman Dave Archambault said he and Kirchmeier have met many times and each meeting has been tense and unproductive. “I don’t think aggressive force is necessary and he thinks it’s necessary,” Archambault said.

In the most recent clash between police and protesters, which was near the path of the pipeline and happened last week, officers used tear gas, rubber bullets and large water hoses in freezing weather. Organizers said at least 17 protesters were taken to the hospital, some for hypothermia and one for a serious arm injury, and one officer was injured.

Archambault called the confrontation an act of terror against unarmed protesters that was sanctioned by Kirchmeier.

“His job is to protect and serve, not to inflict harm and hurt,” Archambault said.

But Kirchmeier, who has the backing of the state’s Republican governor and attorney general, defended officers’ actions. He and other authorities said officers were assaulted with rocks, bottles and burning logs.

Kirchmeier, a 53-year-old married father, grew up in this county, which has a population of fewer than 30,000 people — about 15 residents per square mile. He retired from the North Dakota Highway Patrol as a captain after 29 years, and had served in the National Guard for four years.

The protests are demanding: Kirchmeier hasn’t had a day off since August, routinely working more than 12 hours a day. The 34 deputies in his department are pulling similar shifts, he said, even with help from more than 1,200 officers from North Dakota and nine other states.

Some officers have been targeted online by protesters, Kirchmeier included. He said someone recently posted the location of his father’s grave, which he took as an effort to intimidate.

“Social media has been very bad and it has turned out like law enforcement is building the pipeline,” he said. “I can’t stop the pipeline. My job is to enforce the law.”

President Barack Obama raised the possibility of rerouting the pipeline earlier this month, and construction on the last remaining large chunk, which is on federal land near the reservation, was halted by the Corps for the time being. But Kelcy Warren, CEO of pipeline developer Energy Transfer Partners, told The Associated Press the company won’t do any rerouting.

Kirchmeier, like many other of the state’s elected officials, blame the Obama administration for not stepping in.

“The issue of the pipeline is not going to get solved with protesters and cops looking at each other,” Kirchmeier said. “This is bigger and takes way more political clout than what the county has to offer.”

Attorney General Wayne Stenehjem said Kirchmeier is in “an incredibly difficult position.”

“He has the responsibility to allow people to lawfully exercise their First Amendment rights and he has the obligation to stop it when there is violence contrary to the law,” Stenehjem said. “And now there are a significant number or lawless people and the citizens are worried.”

Gov. Jack Dalrymple said Kirchmeier “has done a remarkable job dealing with all the issues brought about by these protests. He has been totally professional in what is not a typical law enforcement challenge in North Dakota.”

With winter looming, the Corps has decided to close the land north of the Cannonball River where the Oceti Sakowin protest encampment have flourished on Dec. 5, also citing the confrontations between protesters and authorities, according to a letter Archambault said he received.

“To be clear, this means that no member of the general public, to include Dakota Access pipeline protesters, can be on these Corps lands,” the letter provided by the tribe said.

The Corps said in a statement Sunday that has “no plans for forcible removal” of protesters and that it “is seeking a peaceful and orderly transition to a safer location.” The agency says anyone on the property north of the Cannonball River after Dec. 5 will be trespassing and subject to prosecution.

Protest organizers said Saturday that they don’t intend to leave or stop their acts of civil disobedience.

Kirchmeier said before the Corps’ move that North Dakota residents who have grown tired — and increasingly afraid — of the protests are backing law enforcement.

“People don’t want their livelihoods disrupted,” he said. “They are not taking this lightly.”

Free Range Report

Free Range Report