“Our national forests are dying from neglect. Rather than channeling dollars to active forest management to reduce the risk of wildfire, the Federal government must spend its funds defending sound management practices from this perpetual environmental litigation machine.” ~Rep. Tom McClintock

House Committee on Natural Resources Press Release

Policy Overview

♦The U.S. Forest Service is entrusted with managing 193 million acres1 of mostly forested areas in 43 states and Puerto Rico.

♦Currently, Fifty-eight million acres of national forest are at high or very high risk of severe wildfire3 due in large part to a lack of active management of the landscape.

♦When District Rangers, Forest Supervisors and their staffs attempt to advance forest thinning and other active management projects, their efforts can be significantly delayed or derailed due in large part to ever increasing environmental analysis requirements resulting in longer, more costly planning timelines and significantly increased regulatory complexity.

♦Ever-increasing analyses are a direct result of attempts by the Forest Service to make environmental analysis documents “bullet-proof” in an increasingly litigious landscape.

♦As reported in the Helena Independent Record, “the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), Endangered Species Act (ESA) and National Forest Management Act (NFMA) are most often cited as the basis for litigation.”

♦Vegetative management activities account for more than 40 percent of all lawsuits brought against the Forest Service.

♦According to a Government Accountability Office (GAO) analysis of data provided by the National Association of Environmental Professionals, the Forest Service produced 572 Environmental Impact Statements (EIS) between 2008 and 2012, nearly 25 percent of all draft and final EIS produced during that time period.

Panel Examines Negative Impacts of Excessive Litigation on Forest Health

WASHINGTON, D.C., June 8, 2017 –

Today, the Subcommittee on Federal Lands held a hearing to examine how litigation and increasingly excessive environmental analysis facing the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) has exacerbated the ongoing forest health crisis.

♦“We are bankrupting the future,” witness Lyle Laverty, Certified Forester and President of the Laverty Group, said. “America’s green infrastructure is on life support, perhaps even on the brink of ecological collapse.”

58 million acres of national forests are at high or very high risk of severe wildfire. Despite deteriorating forest health and the increasing potential for catastrophic wildfire, USFS employees spend more than 40 percent of their time conducting planning and analysis instead of managing our federal forests and rangelands.

♦“[O]ur national forests are dying from neglect,” Subcommittee Chairman Tom McClintock (R-CA) said. “[R]ather than channeling dollars to active forest management to reduce the risk of wildfire, the Federal government must spend its funds defending sound management practices from this perpetual environmental litigation machine.”

Environmental laws originally intended to protect the environment, such as the National Environmental Policy Act and the Endangered Species Act, are now working against the USFS, significantly hindering active management.

♦”This has contributed to the decline of the very resources the laws are intended to protect,” Laverty stated. “Unnatural fuel accumulations lead to the uncharacteristic wildfires that can and will ultimately harm listed species and water quality.”

The panel outlined how excessive lawsuits and vague statutory authorities force the USFS to make environmental analysis documents “bullet-proof,” in fear of litigation.

In this litigation-prone climate, Laverty argued the federal focus “has been mostly prevention of harm from action. The potential for harm from inaction has largely been ignored.”

Another witness, Lawson Fite, General Counsel for the American Forest Resource Council, argued that a large percentage of lawsuits aren’t targeted as specific legal violations, but are instead used by self-proclaimed environmental groups to halt or prevent restoration activities.

♦“They force the agencies into years-long paperwork exercises that result in no project changes or conservation benefit,” Fite said.

♦“They have succeeded... It might be making environmental attorneys rich, but it is killing our forests,” McClintock added.

♦Fite, however, offered hope, describing forestry as “an area of bipartisan progress” noting: “There are a number of measures with support from Republicans and Democrats, environmentalists and industry, which can streamline environmental compliance while preserving a right of review and protecting resources such as watersheds and wildlife. The time for action is now.”

♦”Healthy forests are a win-win-win situation,” Rep. Westerman (R-AR) stated. “We should all be able to work together to manage our forests in a healthy, sustainable manner for everyone’s benefit.”

Video of full hearing

Background

America’s 154 national forests are increasingly becoming overgrown, insect and disease infested, fire-prone thickets due in part to a lack of active management, such as thinning forests, to promote resiliency and enhance forest health.

Service Chief Tom Tidwell indicated, “58 million acres of national forest are at high or very high risk of severe wildfire” – or nearly one third of all of the Forest Service’s acreage and an area roughly the size of Pennsylvania and New York combined.

The Forest Service’s anemic forest management efforts, both in terms of administrative obstacles (e.g., cumbersome planning processes, high costs and analysis paralysis); and legal obstacles in approving forest management projects, exacerbate the ongoing forest health crisis.

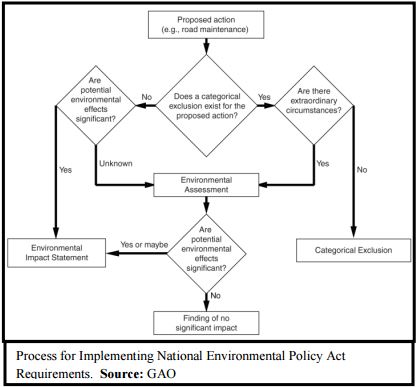

National Environmental Policy Act Process and “Analysis Paralysis”

Timelines for analysis have increased from several months to several years for a typical forest management project. In March of 1981, the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) published guidance to federal agencies noting that the preparation of an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for “even large and complex energy projects would require only about 12 months”and went on to note that completion of an Environmental Assessment (EA) “should take no more than 3 months.” However, a 2014 report by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) noted that the average EIS now takes more than 4.5 years (1,675 days) to complete and that time to complete is increasing at a rate of more than 34 days per year. The timeframe for completing NEPA analysis under an EA or Categorical Exclusion (CE) has not fared much better over time, with the Forest Service reporting to GAO it takes more than 18 months (565 days) to complete an EA and nearly 6 months (177 days) to complete a CE.

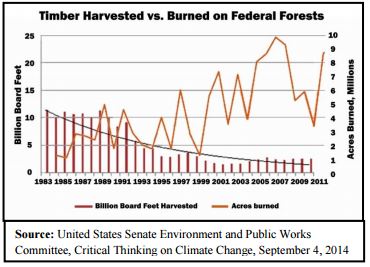

Today, increasing NEPA analyses requires the Forest Service to expend significantly more time and resources to complete what CEQ once referred to as “concise public documents.” As more and more Forest Service resources are consumed by regulatory analysis, scarce agency resources are expended, fewer acres of forest are treated and fewer products harvested from our forests. As the flow of forest products has declined, lumber mills that once supported local economies have closed, forest jobs have disappeared, our forests have become over-grown and fire prone and catastrophic wildfires have increased in size and severity.

In 2002, then-Forest Service Chief Dale Bosworth, requested a study be conducted to assess the agency’s “analysis paralysis.” The report, “The Process Predicament, How Statutory, Regulatory, and Administrative Factors Affect National Forest Management,” describes an agency in which “excessive analysis” contributes to delays, confusion and increased costs and where staff spends nearly half of their working hours conducting environmental analysis to “bullet-proof” projects against litigation. Sadly, the points made by the report are just as salient today as they were the day the report was published.

In an attempt to make modest strides toward addressing the “analysis paralysis” challenge, the Forest Service has promoted stewardship contracting as a means of conducting necessary forest thinning projects, and is investing time and resources to support locally based forest collaboratives, which seek to bring diverse groups of stakeholders, such as industry, environmental groups and local governments, together to develop forest health projects and find solutions to complex natural resource management challenges.

Unfortunately, litigation persists. As Madison County, Montana Commissioner Dave Schulz noted before the Federal Lands Subcommittee in May of 2015, due to the threat of litigation from outside groups refusing to meet or collaborate with the community, what started as a consensus proposal for 100,000 acres of fire salvage and reforestation was reduced to less than 2,000 acres of salvage. “Fear of litigation prevents the Forest Service from thinking big” and is a “significant factor in preventing responsible management of our Nation’s forests.”

Litigation’s Paralyzing Impacts on Federal Forest Management

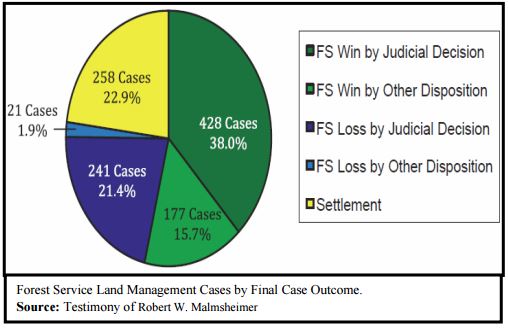

Litigation is paralyzing one of the core missions of the Forest Service. Between 1989 and 2008, 1,125 lawsuits were filed against the Forest Service. Hundreds more have been filed since. Although more than 80 laws govern the management of the national forests, NEPA, the ESA and NFMA are the laws most frequently cited in litigation against the Forest Service with NEPA cited in more than 71 percent of cases.

Litigation is among the most often cited reasons for NEPA related project delays and both litigation and the threat of litigation can cause significant delays. An agency official seeking to prepare a “bullet-proof” EA or EIS must be mindful of not only federal rules and regulations but also previous judicial interpretations. Even so, outside observers note that the sheer number of federal rules and regulations governing a federal project make it almost certain a judge will find some part of the process as deficient. This causes over-correction, additional regulation and leads to “an increase in the cost and time needed to complete NEPA documentation, but not necessarily an improvement in the quality of the documents ultimately produced.”

What’s more, obstructionist litigants know that a successful case is not required in order to delay or halt a forest management project for months, years or indefinitely. Of cases brought against the Forest Service between 1989 and 2008, the Forest Service prevailed in 53.8 percent of all cases and nearly two-thirds of cases in which a judge ruled on the merits of the case. In fact, the Forest Service only lost 29.8 percent of cases brought against it. These relatively low chances for success led Dr. Robert Malmsheimer to conclude before the Federal Lands Subcommittee that “the indirect benefits of litigation, such as publicity and delay of Forest Service action, may be as important to litigants as the direct benefits of winning a case.”

Devastating Impacts on our Federal Forests

Today, lawsuits intended to halt active management of federal forests account for more than 40 percent of all lawsuits brought against the Forest Service.

From the mid 1950’s through the mid 1990’s, the amount of timber harvested from the national forests averaged 10 to 12 billion board feet. In FY 2015, the Forest Service harvested less than 2.9 billion board feet of timber across 204,763 acres, a small fraction of the acreage in need of treatment. Beginning in 1996, the average amount of timber harvested from federal forests fell to between 1.5 and 3.3 billion board feet. Conversely, since 1996, the average annual amount of acres burned due to catastrophic wildfire totaled over 6.2 million acres per year.

Today, while Forest Service employees at the national forest level spend more than 40 percent of their time conducting planning and analysis instead of actively managing our federal forests, more than fifty percent of the Forest Service budget is spent fighting catastrophic wildfire. In 2015, wildfires burned 10.1 million acres of forests, including 7.4 million acres of federal lands.

Agency staff rate catastrophic wildfire as one the biggest threats to endangered species habitat and as wildfires continue to increase in size, number and intensity, their adverse impacts to wildlife habitat grow as well. Hot, long burning fires burn nutrients out of the soils and reduce water retention, both of which are critical to the reestablishment of vegetation after a fire. Mudslides, flooding and erosion, which often occur on the heels of a severe wildfire, threaten water availability and water quality for forest wildlife and human populations alike.

The direct costs to the Forest Service for responding to the impacts of catastrophic wildfire, including landslides, flooding and other threats to life, property, water quality and ecosystems have topped $166 million from FY 2011 to FY 2016. This figure does not include costs to private lands owners, counties, municipalities and water districts.

The impact of wildfires devastates homes, businesses and communities as well. Between 2006 and 2016, the Forest Service reported that wildfires destroyed 36,827 structures. In the last two years alone, wildfires burned nearly 9,000 structures. Tragically, there have also been 349 wildfire-related fatalities over the past twenty years.

This hearing seeks to further explore the plethora of problems facing the Forest Service and our nation’s federal forests.

Download full PDF with footnotes here:

Free Range Report

[wp_ad_camp_3]

A perfect example is Summit County Colorado and the devastation from the pine beetle. Its amazing that lightning has not burned the whole county and the multi million dollar homes. The problem spread to Gore Range and beyond in the last 15 years. Sad to think that some of the mountains are gray not green from dead weathered trees.

Typical forest service BS. They lock them up and burn them down. Okanogan County is a perfect example.