Martin said that if all tax money stayed within the county, the system might not be so bad. But since the state gets some of the county’s tax money, and the state is shuffling money into different pots, the system seems inequitable for Fall River County ag producers.

With ranchers paying corn ground rates on land being used as grassland, this can become an issue, Martin said.

John D. Taylor Hot Springs Star

Agricultural tax issues could cause problems in Fall River County

HOT SPRINGS | Two tax issues are coming to a head across Fall River County. Thanks to state mandates, agricultural producers — especially ranchers — are continuing to get hit with rising property valuations based on soil-type analysis. Also, some subtle shifts in who pays what in terms of overall county taxes are taking place, according to a recent report.

Ranch impact

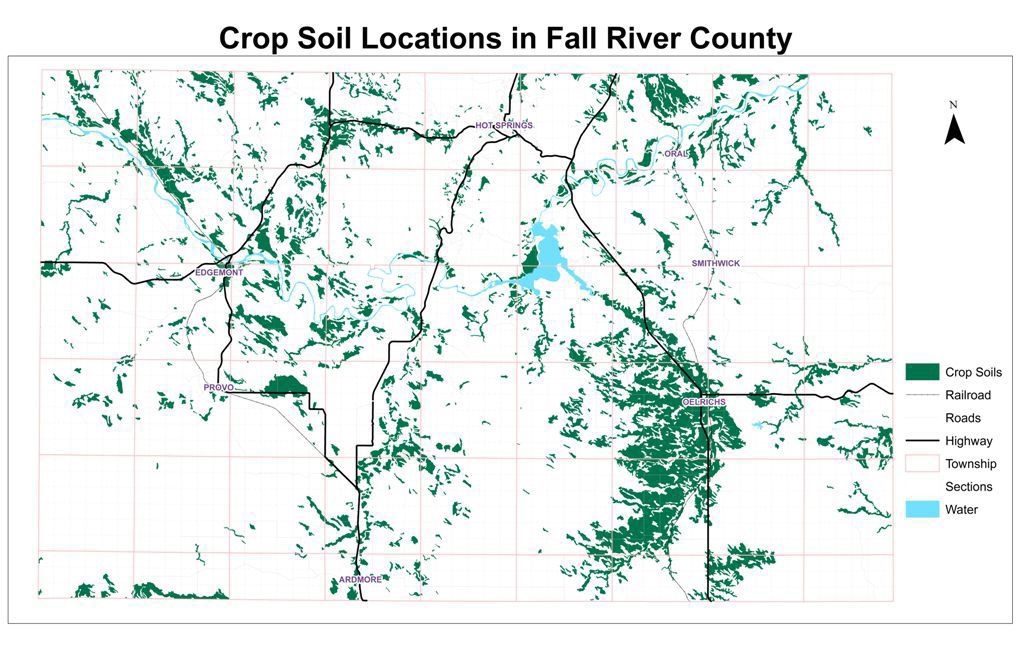

Fall River County geographic information systems coordinator and public information officer Stacey Martin has a map of what ought to be crop land across Fall River County, based on the type of soils that are involved. Green on this map designates land that should be cropped — and there’s a lot of green on Martin’s map, especially around the Oral irrigation district, and all around Oelrichs.

The trouble is, this map doesn’t represent actual land use, only soil types and what land should be cropped — not what is cropped — according to soil types. The actual use of much of the land shaded in green on this map is cattle pasture, range lands and beef production.

Another issue: According to the state Department of Revenue, this map indicates how agricultural ground should be valued and, hence, taxed.

Crop ground, according to the state’s way of thinking, has a higher value than grasslands because of its productivity potential. Stick a bunch of corn, wheat, sunflowers, soybeans or other crops in those green spots, and you’re likely to earn more than you can by raising cattle or sheep there.

As a result, when county director of equalization Susie Simkins is charged with making sure that people’s property valuations are accurate, she is obligated by the state to value those green spots on the map at higher values than the white splotches on Martin’s map.

The reason these lands are not cropped, Simkins says, can vary: lack of access for farming machinery, an isolated location, or simply a landowner choosing to raise cattle because sticking sunflowers into the 50-acre green patch in the middle of his cow pasture just doesn’t make sense.

Simkins can adjust valuations down somewhat for some green, should-be-cropped areas. But since 2010, when the state law requiring her to value agricultural lands on the basis of crop or grass went into effect, the state has been strongly pushing her to get land values up to 100 percent based on soil types, not land use.

How this creates problems for Fall River County agricultural producers, according to both Martin and Simkins, goes something like this:

Say Rancher Jones has a section of ground where he runs red Angus beef cattle and half this ground is potential soil-based crop ground.

His neighbor, Rancher Smith, also runs red Angus on the section adjacent to Jones’ cow pasture.

Jones’ property valuation — and his taxes — are going to be significantly higher than Smith’s because Smith’s land is valued at grass rates, whereas half of Jones’ land is valued at cropland rates.

Also, Simkins said, the spread between the values of grass vs. crop soils is growing.

However, while soil type land valuations work well in the East River region, where 70 percent of the state’s population lives, they don’t work nearly as well in West River.

Soil type valuations can even be counterintuitive in the Black Hills.

Martin pointed to valuations in the Black Hills where sales figures as well as soil types come into play when assessors are valuing lands. Since the Black Hills region is a popular place to live, property here can, and usually does, have very poor soils, yet it is still valued higher than prairie land with crop soils, because of the way property sales figures affect valuations. Meanwhile, a nearly equivalent parcel of Black Hills land with crop-able soils might actually have lower valuations if it is in a location with fewer sales.

Martin said virtually all of the West River counties are experiencing some pain based on soil-type land valuations vs. actual use valuations.

“Actual use is a naughty word,” said Simkins, when it comes to getting the state to change the system. She and County Commissioner Joe Falkenburg testified in 2015 to try to get legislators to modify the valuation system to be fairer to West River residents. But lobbyists keep pushing for ranchers to continue to pay “corn ground” rates.

Martin said that if all tax money stayed within the county, the system might not be so bad. But since the state gets some of the county’s tax money, and the state is shuffling money into different pots, the system seems inequitable for Fall River County ag producers.

With ranchers paying corn ground rates on land being used as grassland, this can become an issue, Martin said.

At a recent county commission meeting, Falkenburg worried that when the soil-type valuation effort finally “sunsets” and 100 percent of valuations are going to be required by the state, ranchers are going to take a big hit, creating another crisis for the county.

Theoretically, if ag lands increase in value, the tax mill levy should decrease some, Falkenburg noted.

“It’s not going to be pretty,” Simkins said.

Tax Shifts

Martin has some other charts that show some interesting things, one of them being a subtle shift in who — agriculture, residential, commercial, etc. — pays what percentage of taxes in the county.

The common assumption among most in Fall River County is that agriculture pays the bulk of the taxes. Yet Martin’s charts, even going back to 2010, don’t bear this out.

In 2010, the value of taxable land across the county accounted for nearly $414 million. Of this, agricultural lands, ag dwelling lands and commercial agricultural property accounted for nearly $104 million, or roughly a quarter, of the overall value of county lands. Residential property was $210 million, almost 51 percent. Commercial property was nearly $48 million, or nearly 12 percent, and utility property was $51 million, also 12 percent.

By 2017, the value of taxable land across the county tallied $556 million. Again, agricultural lands and ag dwellings amounted to 29 percent of the value, ($162 million in value), and residential property was 49 percent (nearly $273 million). Commercial property was nearly 9 percent ($48 million), and utility lands represented 13 percent ($72 million).

Taxes levied during this same time frame show similar shifts.

Another shift plotted by Martin is where county ag lands hold the most value. She created a map to show ag land value shifts from 2014 to 2017, following reassessment. Roughly speaking, ag lands in the eastern portion of the county have risen in value, and while western ag lands have decreased in value.

Each year, Martin also likes to find properties spread across the county that are very similar in size, land mass and use, but taxed at different rates and compare non-ag taxes with ag taxes.

On the three parcels she shared, the ag taxes, which are historically low, and the non-ag taxes, which are among the highest tax rates paid, were astonishing.

One Black Hills comparison of two 40-acre parcels showed two nearly adjacent properties, one ag, one non-ag where non-ag taxes were 16 times the ag tax. A Provo-area comparison showed non-ag taxes being seven times the rate of the ag taxes. And an Edgemont and Hot Springs comparison show two 40-acre parcels where the non-ag taxes were 14 times the rate of the ag taxes.

Martin said she couldn’t speculate on the meaning of these disparities, but said people paying the non-ag taxes were getting the “fuzzy end of the lollipop.”

It is absolutely the case that the tax burden is unequal. I long for a repeal of the taxes that grossly target industrialized states like California and New York to pay farm subsidies to states like South Dakota that constantly take in more than they pay in taxes in order that people can continue inefficient agricultural models that allow for cheap political points.

The sooner this inequality ends, the better.