…when the Murr children approached St. Croix County in 2004 to sell the vacant lot to finance improvements at their parents’ cabin, they were told they could neither sell nor develop the property thanks to regulations put in place in the 1970s.

A 1975 county ordinance based on state regulations required a total area of at least an acre to develop. After wetlands and floodplains were subtracted, the Murrs’ lot was too small to develop.

Amanda Reilly

Justices appear split in Wisconsin waterfront fight

The Supreme Court heard arguments today in a fight over a riverfront lot in Wisconsin with potentially major implications for how courts weigh whether the government has illegally taken private property.

The court’s liberal wing appeared skeptical of the claims of the family who say the state’s restrictions on their ability to sell or develop a vacant lot along the St. Croix River amounted to an illegal taking.

But conservative justices hurled their toughest questions at attorneys for the state and St. Croix County. Justice Anthony Kennedy, who wrote the opinion in the court’s last major property rights case, could be the deciding vote.

At issue in today’s arguments is a legal concept from a 1978 Supreme Court case, Penn Central Transportation Co. v. New York City, which says courts shouldn’t divide a single parcel when weighing the extent that private property rights might have been violated. Courts instead were directed to weigh the taking against the “parcel as a whole.”

In the current case, Murr v. Wisconsin, the court must decide how much weight to give state property lines in the “parcel as a whole” analysis.

If the justices rule in favor of the landowners, the Murrs, it could make it easier for property owners and developers to win in future takings claims against the government. States are split on the issue: Nine led by California support Wisconsin, while nine led by Nevada support the Murrs.

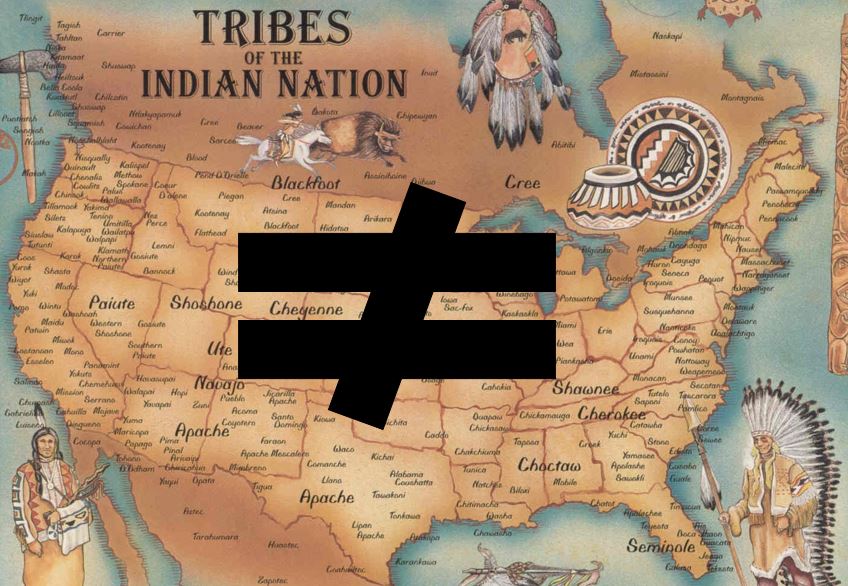

The case revolves around two adjacent properties that the late William and Dorothy Murr separately purchased in the 1960s along the St. Croix River, a 169-mile tributary of the Mississippi River (Greenwire, March 17).

The couple built a cabin on one lot for the Murr family’s summer gatherings and left the other approximately 1-acre lot vacant, planning to hand it down to their children as an investment property.

But when the Murr children approached St. Croix County in 2004 to sell the vacant lot to finance improvements at their parents’ cabin, they were told they could neither sell nor develop the property thanks to regulations put in place in the 1970s.

A 1975 county ordinance based on state regulations required a total area of at least an acre to develop. After wetlands and floodplains were subtracted, the Murrs’ lot was too small to develop.

The ordinance contained a grandfather clause allowing single-family residences to be built on lots created prior to 1976, but only if the property wasn’t under the same ownership as an adjacent lot. Because the Murrs owned the adjacent lot, the clause didn’t apply.

The Murrs sued, alleging an illegal taking of private property. The Wisconsin Court of Appeals ruled against the family, relying on the “parcel as a whole” precedent.

While they argued slightly different positions, Wisconsin, St. Croix County and the federal government urged justices to uphold the ruling. The Supreme Court, they say, should weigh any taking of the Murrs’ vacant lot against their entire contiguous property along the river, which includes the adjacent lot with the cabin.

But the Murrs argue that their two properties — the vacant lot and the lot with the cabin — have remained distinct legal entities. Viewed that way, the government’s barring the sale of the vacant lot is a significant loss.

“There hasn’t been a merger here,” John Groen, a Pacific Legal Foundation attorney who is representing the family, told the court.

Call for ‘flexible, nuanced approach’

Justices from the court’s liberal wing said the Murr children should have known the restrictions placed on the land when their parents transferred ownership of the lots in the 1990s.

Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan said owners of property buy into a certain set of regulations when they own land.

“Ignorance of the law is not a defense anywhere,” Sotomayor said.

Justice Stephen Breyer also said he worried about the implications of issuing a bright-line rule saying state property lines determine the parcel as a whole in takings claims. That could encourage developers, he said, to subdivide large properties in order to stand a better chance at defeating environmental regulations that affect a small area.

And Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg noted that many states have similar ordinances effectively merging property that could be affected.

The court’s conservative wing, on the other hand, questioned Wisconsin’s position that the Murrs’ lots were merged for all relevant purposes under state law.

The state wants the high court to recognize that state laws such as merger provisions shape the relevant parcel as a whole in takings claims.

But Wisconsin’s position on what configurations of property ownership result in merged lots seem “a little quirky,” Chief Justice John Roberts said.

He also said the state was muddling the takings analysis by giving more weight to state merger provisions than property lines.

Kennedy questioned the fairness of Wisconsin’s position and whether state law can change a landowner’s investment-backed expectations. But he also said the Murrs’ theory appeared to ignore market factors.

Elizabeth Prelogar, assistant to the solicitor general at the Justice Department, urged the court to consider multiple factors — and not just state property lines — when deciding the matter.

“It is important to have a flexible, nuanced approach here,” she said.

Wisconsin Solicitor General Misha Tseytlin said there’s one thing on which everyone agrees: “This area of law is incredibly complicated.”