Privately owned farms, ranches, and forests, collectively known as working lands, are the cornerstones on which our nation was built. These lands not only produce much-needed food and fiber while sustaining rural economies, they provide many conservation benefits as well, including clean water, wildlife habitat, and ecological diversity.

THE ROLE OF WORKING LANDS IN PROVIDING PUBLIC CONSERVATION BENEFITS

“Conservation means harmony between men and land,” Aldo Leopold noted in a 1939 address, The Farmer as a Conservationist. “When land does well for its owner, and the owner does well by his land; when both end up better by reason of their partnership, we have conservation. When one or the other grows poorer, we do not.” As Leopold described, it is in the best interest of owners of working lands to care for the land because they rely upon it for their livelihoods. Landowners’ bottom lines are tied to stewardship practices that balance land sustainability and economic viability. Their conservation efforts, therefore, benefit both the environment and their operations.

Privately owned farms, ranches, and forests, collectively known as working lands, are the cornerstones on which our nation was built. These lands not only produce much-needed food and fiber while sustaining rural economies, they provide many conservation benefits as well, including clean water, wildlife habitat, and ecological diversity. These benefit often extend beyond property lines, serving the interests of both landowners and the public. Working lands are able to provide these benefits because environmental stewardship often goes hand-in-hand with crop, livestock, and timber production.

Part I of this two-part collection on private conservation on working lands celebrates examples of ranchers, farmers, and timber producers managing their properties with a conviction for conservation. Their private efforts result in public benefits such as conserving endangered species, improving water quality and quantity, and stopping the spread of invasive species, among others, demonstrating how working lands play a crucial role in wider conservation goals.

While these case studies show conservation on working lands is possible, well-intentioned government policies can instead make it very difficult for landowners to engage in stewardship practices. Part II, Policy Challenges to Conservation, will explore several policies that counter-productively discourage environmental conservation on working lands. It will also pose potential reforms that would make it easier for more landowners to engage in conservation efforts similar to those discussed in these case studies.

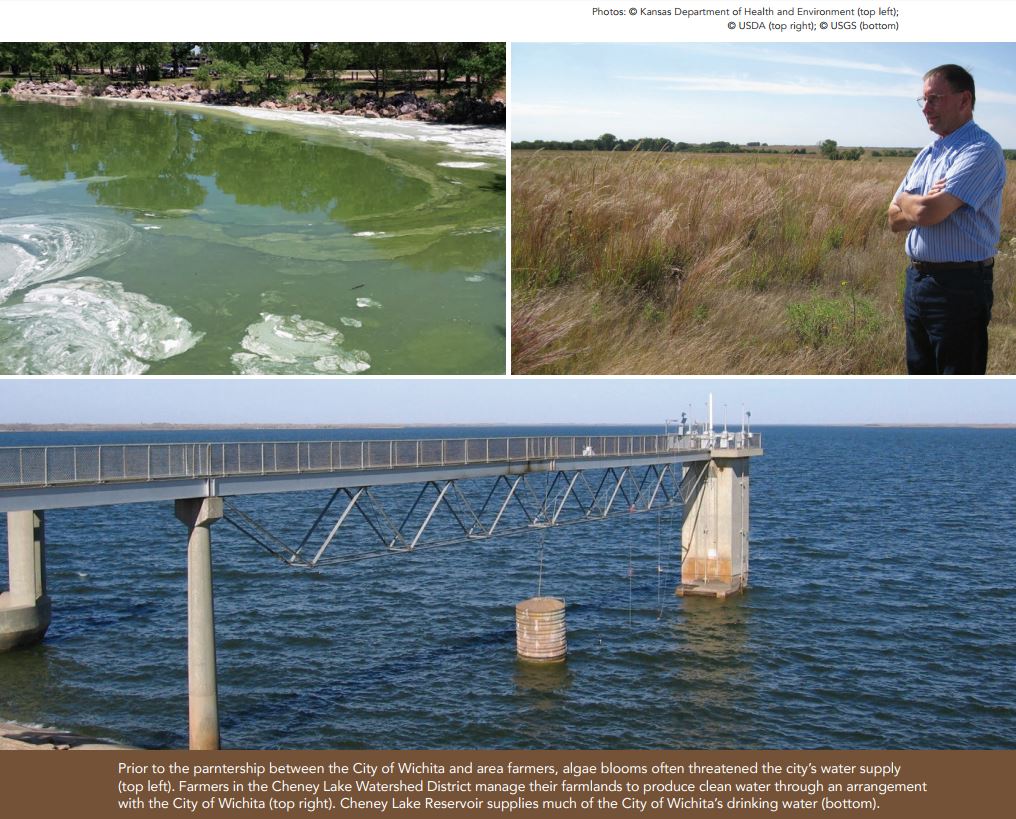

CHENEY LAKE WATERSHED

Local organization farms water quality in Kansas

Agriculture has been big business for farmers in South Central Kansas for decades. Today, thanks to an innovative partnership, farmers in the region are now producing another valuable output: clean water. In the 1960s, the Cheney Lake Reservoir was constructed as part of a project to provide food control, recreational opportunities, and fish and wildlife habitat, as well as supply drinking water to the city of Wichita over the coming century.

The surrounding watershed is a fertile and agriculturally diverse region, supporting everything from small-scale dairies to commercial-scale croplands. It also provides 60 to 70 percent of the city’s daily water needs. In the early 1990s, a problem emerged: Algae began to bloom in the reservoir, and Wichita’s drinking water developed a strange taste. Excessive runoff of phosphorus and other nutrients applied to crops created the algal blooms, and erosion from farms and stream banks increased sediment buildup and reduced the reservoir’s storage capacity. Residents, farmers, and the City of Wichita began to recognize that the region’s water quality could no longer be taken for granted. The environmental and economic costs of poor water quality were far reaching.

Dirtier water increased water-treatment costs for the City of Wichita and also compromised the environmental quality of the watershed, harming local fish and wildlife habitat and limiting opportunities for recreationists. In 1994, the Reno County Conservation District formed the Citizen Management Committee, a farmer-led organization tasked with implementing a watershed plan to reduce sediment loading and phosphorus runoff by 40 to 45 percent. The goal was to double the life of the reservoir.

Five years later, the committee established the non-profit Cheney Lake Watershed to provide education and assistance to landowners interested in improving water quality. The non-profit works with farmers to inform and assist in the voluntary implementation of best management practices that can be incorporated into farming activities to protect water quality and prevent erosion. The aim is to improve water quality while preserving agricultural production.

Officials in Wichita understood that the city’s water quality would improve and its water treatment costs would fall as more farmers implemented the best management practices, which include planting native grasses, creating waterway systems for livestock other than natural creeks, and wetlands development. To encourage the farmers to get on board, the city worked with the Cheney Lake Watershed to reimburse 30 to 40 percent of farmers’ costs for the management projects. The city also funded up to 50 percent of the costs for landowners to install perimeter fencing to maintain grasslands established under the federal Conservation Reserve Program. The cost-share program took off. In the nearly two decades since the Cheney Lake Watershed was established, local farmers have implemented more than 2,000 management projects across 80,000 acres of the watershed.

The types of projects implemented on a given farm vary depending on the specific features and management of it, but many farmers are currently planting cover crops and converting to no-till farming practices to reduce erosion and phosphorous-laden runoff. The program continues to thrive today, completing 50 to 75 projects each year with Wichita’s financial assistance.

© USDA (top right); © USGS (bottom)

Though the success of these practices varies depending on rainfall patterns and weather events, the arrangement has been largely successful. The City of Wichita reports fewer algal blooms in its water, and the Department of Health and Environment reports lower phosphorous levels in the reservoir. The Cheney Lake Watershed also says its work is creating a culture of conservation among farmers by encouraging them to consider water quality in their operational decisions. Not only has the cost-share arrangement between Wichita and farmers been good for the environment, it has also benefited both parties. Farmers improve their land-use practices and potentially increase their economic returns, while the city reduces water treatment costs and extends the lifespan of the reservoir.

Through an innovative contracting arrangement, those who demand and supply water have collaborated to solve the problem of algal blooms in Cheney Lake and provide the City of Wichita with clean drinking water.

[paypal_donation_button]

Free Range Report

[wp_ad_camp_3]

[wp_ad_camp_2]