Over eight decades later, Jones still remembers the day the federal government killed the sheep. In 1934, as part of former President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal, the government decided the Navajo had more livestock than the Southwest could support. According to some estimates, 80 percent of all Navajo livestock were killed, and thousands of Navajos impoverished.

American Indians fight for land rights against Obama’s executive decrees

Betty Jones, an elderly Navajo medicine woman, grew up among the red rock canyons, mesas, and ancient cliff dwellings of Southeastern Utah. Now, a proposed national monument may prevent her from collecting traditional herbal medicines she’s gathered all her life.

Her family believes Jones is in her mid-nineties, since her birth certificate was issued after her actual birth. The proposed 1.9-million-acre Bears Ears National Monument would potentially limit her access to sacred sites and impact herb collection. She also says that she is entitled to grazing rights on the land under an agreement with the federal government dating to the 1940s.

“My late husband was promised access to the land for sheep grazing and it’s wrong for Washington to go back on its word,“ she says. Nearby, her daughter unrolled maps and opened old letters to prove the claim.

The Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition, a coalition of five tribal councils, with support from environmentalists, is pushing for the creation of the Bears Ears National Monument. Following a field hearing in Utah, Secretary of the Interior Sally Jules said she was “shocked” the area was not better protected.

As a result, the Obama administration seems poised to create the new monument by proclamation — a power granted to the president under the 1906 Antiquities Act. The proposal takes its name for two 9,000 foot buttes that, from a distance, resemble bear ears. San Juan County is the largest county in Utah and also its poorest. The largest city in the county is Blanding, a town of 3,500 people. Locals feel it is outsiders who are pushing the monument proposal.

Local Navajos disagree with the Navajo Nation, opposing the plan. Navajos who live in the area fear they will lose access to land that they have used for centuries for religious ceremonies, grazing, hunting, and wood-collecting. Members of the local Ute tribe share these concerns. Other opposition comes from civic groups and residents who worry about their own lost access and its economic impact.

“This community would support a smaller monument,” says Jami Bayless, president of the Stewards of San Juan County. “However, the proposed monument is bigger than the State of Delaware. Any visitor here can see that this a beautiful area that is already protected by numerous laws and by locals who love this area.”

Bayless’s Non-governmental Organization (NGO) was formed last month to ensure local residents had a say in public policy about the area.

The Day The Feds Killed The Sheep

Over eight decades later, Jones still remembers the day the federal government killed the sheep. In 1934, as part of former President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal, the government decided the Navajo had more livestock than the Southwest could support. According to some estimates, 80 percent of all Navajo livestock were killed, and thousands of Navajos impoverished.

In traditional Navajo culture, sheep are virtually sacred, and both men and women maintain flocks. Throughout her life, Jones and her family have struggled to maintain their livestock. She believes the monument would be another blow to the Navajo way of life.

“My husband and I would graze our flocks in the land that is now Bears Ears,” she says. Jones speaks only Navajo, and her objection to the monument proposal was translated by her daughter, Anna Tom, whose home Jones is visiting.

The home is a three-room dwelling on the edge of the Navajo Nation in southern Utah. Only a few other Navajo homes are visible in the area, which is dotted with thorny bushes and dry gullies where water once flowed. A generator provides intermittent electricity. Like many on the reservation, she does not have access to running water.

As Jones spoke, her relatives worked a dozen yards away to finish the roof of a Navajo hogan, or ceremonial lodge, ahead of a forecasted storm. In preparation for the storm, a small pile of wood is stacked next to a heating stove. A cardboard scrap will serve as kindling.

The Bears Ears issue has divided the Navajo people, who refer to themselves as the Diné. The government of the Navajo Nation supports the monument. The Aneth Chapter and the Blue Mountain Diné, the two Navajo groups who live closest to the proposed Bears Ears Monument, both oppose it. The latter is also not an officially recognized entity within the Navajo Nation.

“At one level, this is a struggle between the state of Utah and the federal government,” says Matt Anderson, an analyst at the Sutherland Institute. “That tension is paralleled among the Navajo. While the Navajo Nation supports the monument, the local Navajo oppose it.”

Anderson believes the proposal is being pushed by outside interests, including outdoor recreation retailers.

“The interest of retailers –who make stuff in China– are being privileged at the expense of local jobs and potential energy jobs.”

The pro-monument coalition includes some tribal government groups, green advocacy groups and outdoor retailers, like Patagonia and Black Diamond Equipment. An investigation by Deseret News found that much of the funding of the monument campaign came from out-of-state, including a portion from the Leonardio Di Caprio Foundation.

Peter Metcalf, the founder of Black Diamond Equipment, is a vocal supporter of the Bears Ears National Monument Proposal.

“Utah is a Mecca for building strong, vibrant outdoor companies,” he wrote in a statement posted on Patagonia’s website. “Our politicians really don’t recognize that these iconic wildlands are not just about biodiversity or watersheds, but they are the backbone of one of the fastest growing economic sectors in the state.”

Wood Cutter Worries

Byron Clarke, the vice president of the Blue Mountain Diné, guides his pick-up truck up a dirt road into the high country around Blanding, Utah on a chilly evening in late November. Snow was visible on the slopes above. Two Christmas red permits, which give him the right to collect wood, were displayed on his dashboard.

The bullet holes in a mile marker were the only visible sign of human impact in the woods along the road. Byron’s eyes scanned the alpine woods for deadwood he is allowed to collect. Finding some, he quickly got to work with his chainsaw.

Local Navajo have hunted, collected firewood and gathered pinion nuts here for centuries — all activities that will be restricted or prohibited if the area becomes a national monument. A large sign at the nearby Arches National Monument makes it clear that wood collecting is prohibited there.

“I take wood down to the reservation every winter,” Clarke says. “There are a lot of poor and elderly Navajo who can’t come down here and collect wood. Some of those elders depend on this wood to get through the winter.” On the Navajo Nation, the official poverty rate stands at 43 percent.

While the monument agreement may include provisions to allow grazing and wood-collecting, for most locals its déjà vu. In 1996, former President Bill Clinton created the Grand Escalante Staircase National Monument, resulting in limited access to wood-collecting and grazing.

An Area Already Rich In Monuments

San Juan County already contains three national monuments, a national park, and a national recreation area. Locals worry that creation of a new national monument will have a devastating impact on the local school system. The state of Utah includes a patchwork of school trust lands held by the state to fund education.

“The proposed Bears Ears Monument will mean the loss of 167,000 acres of school trust lands that, if we lose access to that, we will lose access to funding for our schools,” said Merri Shumway, vice president of the local school board. “If the quality of education suffers, we lose the best hope to improve the economy. There is also the indirect impact of the lost jobs. The government is the largest employer in the county.”

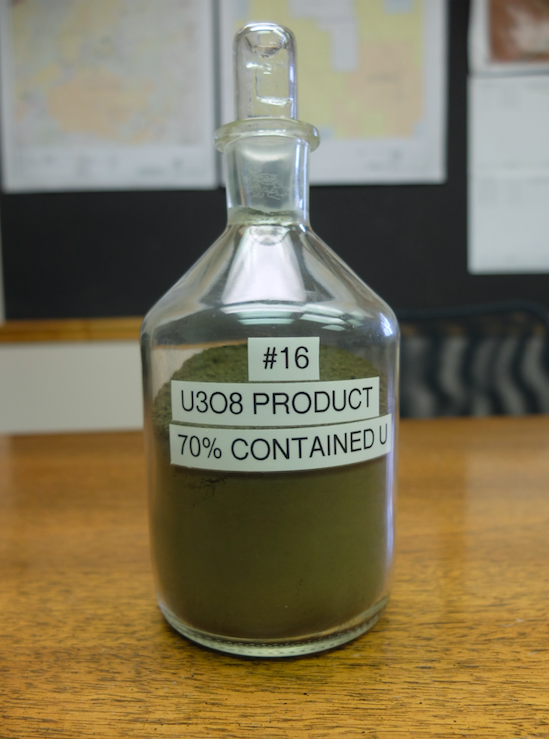

The largest private employer in the county is Energy Fuels Resources. The company runs a uranium mill just south of Blanding and has mining claims within the area of the proposed monument. As recently as three years ago, the facility processed ore from an active mine on land that lies within the borders of the proposed monument. Then, uranium prices collapsed. Today, the market price for uranium is $18.50 a pound — roughly half of what it was a year ago. The Sierra Club has targeted the mine as one of the reasons it supports the Bears Ears National Monument proposal.

Back on the Navajo Nation, Jones has her own ideas about how the land will be used if no monument is declared.

“The land is precious. We have to take care of it, and Mother Earth. What I want to do is use the land the way that we have always used the land, and hopefully one day my grandchildren will as well.”

Outside, her grandchildren brought a flock of sheep to a pen. The sheep huddled together, knowing the snowstorm was approaching, and their canine guardians plopped down nearby with tongues extended in exhaustion.

Joseph Hammond Daily Caller News Foundation

Free Range Report