“Equal Access to Justice Act is a taxpayer funded meal ticket for environmental groups to collect attorney’s fees at enhanced rates…It’s an incentive to sue the Department of Interior and other agencies and is a funding source for expansion of the staff and offices of groups that want to halt environmentally and economically beneficial natural resource projects.”

posted by Marjorie Haun

For decades, environmentalist NGO’s have enjoyed a parasitic relationship with the federal government, especially the Department of Interior and its underling agencies. They’ve siphoned billions of dollars out of these agencies’ budgets, and it’s been made possible by abuses of the Equal Access to Justice Act (EAJA), which passed through Congress in 1979 and was signed by President Jimmy Carter in 1980. Although its intent was to level the playing field for ordinary citizens seeking redress for governmental infringements of civil and property rights, chinks in the EAJA have enabled environmentalist groups to get fat off of the American taxpayer, effectively turning the DOI into a perpetual motion money machine funding their radical agendas. Ag, ranching, and other resource-based industry groups have made the case for EAJA reform, including the Farm Bureau, which stated:

…statutes, like the Equal Access to Justice Act, can allow activists to have their court costs reimbursed. In sum, many people have evaluated the existing system and found that it falls critically short in providing the transparency, openness and fairness that the system is supposed to provide.

In November of 2016, the National Association of State Departments of Agriculture, representing more than 50 business and ag interests, penned a letter to the Trump Transition team, which said:

With the expansion of citizen lawsuits, disbursements of public funds from the Judgment Fund have taken on increased significance. Additionally, in 1980 Congress enacted the Equal Access to Justice Act. The statute has the laudable goal of seeking to assure that no stakeholder is foreclosed from access to the court system; but its implementation has been unequal, even arguably unfair. Moreover, particularly for western states, there are increasing complaints that the EAJA has been used to pursue an activist agenda through the courts when such policies fail to win approval on Capitol Hill. This has often occurred in disputes over logging on public lands.

And, a recent report by Strata Policy detailed EAJA abuse by some of the world’s largest environmentalist special interests:

Two facts about the scope of the Sierra Club’s EAJA abuse are necessary to understand.

The first is the extent of the organization’s litigation. Karen Budd-Falen, a Wyoming

lawyer who has brought a lot of focus to EAJA, found that between 1989 and 2009 the

Sierra Club filed 983 suits. (Budd-Falen, 2009, p. 2). EAJA money awarded from those

suits will be explained more later, but for now we will focus on the Sierra Club’s volume

of litigations. The second is how far away the Sierra Club is from the intended group of

EAJA users. In the Sierra Club Foundation’s 2012 tax return, they reported $79.6 million

in net assets (Internal Revenue Service, 2012(a)). This is more than eleven times the size

allowed by EAJA for for-profit organizations. The 501(c)(4) Sierra Club’s own net worth

was unavailable without requesting it directly from the organization or the IRS itself.

Regardless, because the Sierra Club Foundation is a 501(c)(3), its worth bears no impact

in whether or not it qualifies for EAJA.

While the Sierra Club is one of the most active environmental litigants, they do not

necessarily broadcast their legal activity. For public relations, the Sierra Club emphasizes

and advertises its rallies—building up its grassroots appearance—and the results of its

efforts. For example, Sierra Club may boast that it shut down a coal plant but never

mention how it impacted the coal plant’s closure. Linking this kind of litigation to EAJA

is even more complicated with the lack of mandatory centralized reporting. As such, this

case study attempts to make fluent a story that is broken and scattered.

The relationship between EAJA and the Sierra Club is complex, but certain trends are

evident. In this study, four aspects should become clear: first, the ways the Sierra Club has

defined environmental litigation; second, a few select instances where there is

indisputable connections between EAJA funds and Sierra Club litigation; third, general

information about the Sierra Club and its reception of EAJA funds; fourth, the current

goals and movements within the Sierra Club, and the implications of these trends for its

future use of EAJA.

The absurdity and sheer hypocrisy of these abuses is made evident by the fact that, beyond punishing ranching, farming, logging, and extractive industries, environmentalist litigation has actually impeded proper resource management by prohibiting the activities which science dictates are necessary for healthy forests, watersheds, and grazing lands, and the species which depend on them.

On Wednesday, June 28, the House Committee on Natural Resources held a hearing addressing abuses, mostly on the parts of environmentalist NGO’s, of the Equal Access to Justice Act (EAJA), and the impediments excessive litigation place on science-based, proactive natural resources management by Interior Department agencies.

The House Natural Resources Committee summarized the June 28 hearing this way:

“Special interests repeatedly exploit our legal system to further their own agendas and sidestep the legislative and regulatory processes,” Vice Chairman Mike Johnson (R-LA) said.

Mark Barron, an attorney focused on natural resources litigation and environmental law, testified to the frequency with which special interest groups abuse both administrative and legal appeal processes to prevent DOI from fulfilling those requirements.

“These lawsuits divert already limited resources away from the core functions of the agency, [but] they also have significant implications for energy producers and the communities in which the producers operate,” Barron stated. “Oil and gas producers are unable to rely on statutorily prescribed timelines when planning projects and committing investment capital. Projects instead are held in limbo for indeterminate amounts of time until BLM can commit the necessary personnel and resources required to perform essential functions.”

The Equal Access to Justice Act (EAJA) is a decades-old law designed to allow individuals with limited resources to sue the government on a level playing field. However, in practice, EAJA has been consistently exploited by national special interest groups to delay and encumber all types of government actions and reap taxpayer-financed attorney fees, regardless of the outcome.

“EAJA is a taxpayer funded meal ticket for environmental groups to collect attorney’s fees at enhanced rates,” Executive Director of the Western Resources Legal Center Caroline Lobdell claimed. “[It] is an incentive to sue the Department of Interior and other agencies and is a funding source for expansion of the staff and offices of groups that want to halt environmentally and economically beneficial natural resource projects.”

“Originally intended to ease the burden on individuals and small businesses that contest government actions, activist groups now leverage [litigation] as a weapon to paralyze agency actions, finance endless lawsuits, and drain taxpayer dollars away from important programs,” Rep Johnson added.

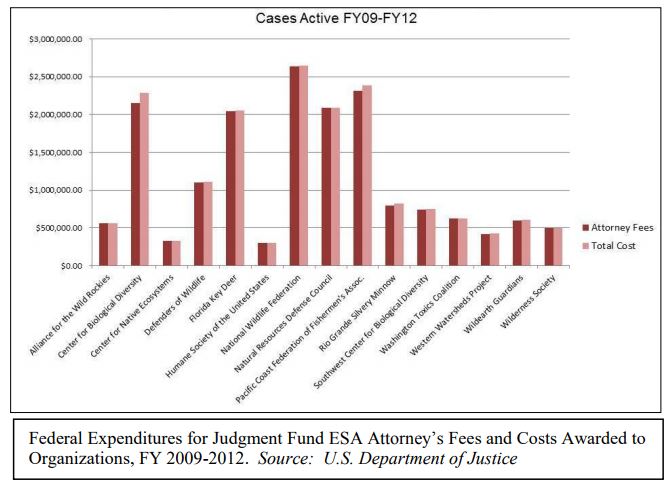

Many of the groups taking advantage of EAJA already boast multi-million dollar budgets and use their activism to raise even more money at taxpayers’expense.

“[T]hey offer a fundraising request every time that there is a lawsuit filed,” Barron said. “It has been prevalent in the media that [these groups] intend to challenge every approval, every permit processing, every implementation of environmental policy under the new administration.”

“If one lawsuit does not succeed, there’s another outfit right around the corner to bring a similar one,” Lobdell added.

Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations Oversight Hearing “Examining Policy Impacts of Excessive Litigation Against the Department of the Interior.

Troubling disclosures from this hearing include:

♦On November 17, 2016, Bureau of Land Management cancelled numerous oil and gas leases by issuing a Record of Decision that included a 2014 settlement agreement. That settlement resulted from six years of litigation, initiated in 2008 when environmental groups challenged the leases. The costs included not only negatively impacted energy development and job growth, but also the Bureau of Land Management’s agreement to pay those plaintiffs $400,000 in attorney’s fees and costs.

♦As a party to litigation, sometimes DOI enters into settlements or receives adverse decisions that require payments to another party. For example, over the past few years, the United States settled claims in excess of $3.3 billion with over 100 Indian tribes alleging federal mismanagement of tribal in-trust assets. In addition to such payments, and as discussed in greater detail below, the federal government may also pay the attorney’s fees and court costs of an opposing plaintiff under certain circumstances. Payments resulting from litigation against federal agencies, including attorney’s fees, may come from that agency’s appropriations or from the Department of the Treasury’s Judgement Fund. In 1956, Congress created the Judgement Fund, a permanent, indefinite appropriation, to serve as a source of payments for monetary awards against the United States, where another source was not already provided.

♦Neither DOI nor DOJ recordkeeping provides much insight into the cost, both in time and resources that litigation against DOI imposes. The long-standing lack of transparency regarding litigation against federal agencies has generated persistent concern. Much of the information concerning this topic lacks important details. In addition to leaving the public uninformed, this also impedes the agency’s capabilities to analyze trends and review information regarding litigation. For example, the SOL does not have a unified case tracking system, and this information is scattered throughout its various divisions. As is the case with information about the litigation itself, records of payments resulting from litigation and settlements fail to paint a complete picture. In 2012, the Government Accountability Office reviewed DOI’s failure to keep records regarding attorney’s fees paid as a result of litigation with the Department.

Free Range Report

[wp_ad_camp_3]