Free Range Report Editorial Staff

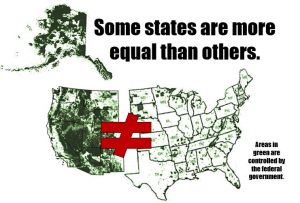

During his terms, President Obama has used the Antiquities Act to create over 25 new national monuments, gobbling up nearly 300 million acres of land, with minimal input from citizens and no congressional oversight.

But San Juan County, Utah, the location of the proposed 1.9 million acre Bears Ears National Monument, has shined a light on the property and human rights struggles resulting from federal land designations.

Consider these voices:

Denton Benn: “The Bears Ears is part of life. That’s the place where our people, our ancestors, even us today we still go up there and do our offerings and prayers. It’s part of our heart and our mind. It’s really sacred to us.”

Chester Johnson: “Bears Ears is special to me because it’s the base of our way of life. Mountain is where songs originate. Mountain provides medicine. Mountain provides food. It’s all there, we just have to search. And this is all provided by the Great Spirit of the Bears Ears. I oppose a national monument because it will have a devastating effect on our life and belief. If President Obama imposes a national monument on Bear’s Ears, and the surrounding region, it will indicate to me that he doesn’t understand the Native Americans that have lived in the area for many years. He will also limit a lot of opportunity that we can use the land to better our community.”

Garry Holiday: “Our people use firewood not only for cooking but also for heating their homes. A national monument would limit the use of our land.”

Susie Philemon: “The federal government again is going to take something, a land that truly belonged to us. They are going to take it away from us again. I really want for my children to go back over there, not just to hunt and pick berries and things like that, but to be able to know that that is where they originated from.” (Excerpts obtained by the Sutherland Institute)

These words, spoken by members of the grassroots Navajo community in San Juan County, comprise a perspective on the proposed Bears Ears National Monument which is not widely covered. The truth is that the proposal has divided the Navajo, and other tribal chapters, of southeastern Utah, and it exemplifies the larger conflicts over public lands, protection, management, and the liberties of those whose lives and cultures depend upon public lands.

If the creation of a Bears Ears National Monument has consequences similar to those of the Grand Staircase/Escalante National Monument, established in 1996 by President Clinton, the residents of San Juan County have great cause for concern. Bill Clinton’s executive “protection” of the massive 1.7 million acre region in southern Utah—which, by the way was carried out in a little publicized ceremony in Arizona—has resulted in economic devastation for the small towns in Garfield County, including the near implosion of the town of Escalante. Restrictions resulting from the Grand Staircase/Escalante Monument’s ‘protected’ status have nearly obliterated local mining and energy sectors, and dramatically reduced grazing, agriculture, and other economic activities.

San Juan County has the lowest median income in Utah, and its poorest locals, many of them from Native tribes, live a semi-subsistence lifestyle dependent on the natural resources and vegetation of the lands coveted by the federal government. The ability to heat their homes with firewood gathered from existing Bureau of Land Management lands, and sell pinion pine nuts to supplement meager incomes, are threatened. But these lands are considered sacred to the locals, and their worries go beyond the potential economic blow to their community. They are alarmed by the restrictions a national monument designation will place on cultural activities in Bears Ears which connect them with their ancestors.

The debate over public lands does not stop with the Antiquities Act and its use in creating more national monuments, it extends to growing environmental, economic, and social concerns across the West. From the implosion of the northwestern timber industry, to the dying town of Escalante, Utah, to arbitrary road closures in Western Colorado, to the introduction of wolves in New Mexico, federal control of Western public lands is dividing states and counties against federal agencies, environmentalist organizations against industries, and citizens against citizens.

Public education of one of the sectors most negatively impacted by federal ownership of lands in the West. The Western Congressional Caucus did an extensive study on the impact of federal control of lands in the West on public education, and concluded:

“One of the often overlooked effects of continued massive federal land ownership is the impact on public education in the West. Even though state and local taxes of western states, as a percentage of personal income, are as high as or higher than other states, there is a persistent shortfall in funding for public education. Part of this is attributed to population growth. An even larger factor in education funding problems for western states is their inability to generate tax revenue due to the vast amounts of federal lands within their jurisdiction. Since public education is heavily dependent on state and local property taxes, western states are suffering.”

But like the grassroots Navajo in San Juan County, states are voicing concerns and fighting back. Lawsuits and legislation in many western states are challenging continued federal control.

Utah is in the process of suing the federal government over what complainants believe is unconstitutional control of over 70 percent of the state. But Utah is also at the forefront of bringing legislation to transfer management of its public lands from federal agencies to equivalent state agencies. With national parks and monuments, tribal lands and Defense Department properties excluded from the transfer proposal, the state and its counties would take control of forests, roads, grazing lands, waterways, and undeveloped regions for protection and management.

When the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 (FLPMA) was passed, Congress acknowledged that those states with significant federal enclaves—virtually every state in the West—would be cheated out of revenues from public lands. Instead of being collected by the states, those taxes would go directly to Washington D.C. The Payment in Lieu of Taxes (PILT) funding plan was created to compensate for those revenues lost to the federal government. But PILT funding is notoriously unreliable and sometimes nonexistent. The Utah proposal would eliminate the need for PILT funding because the state would retain revenues created through management of its own public lands.

Does Utah have the answer for all states in the West? Not necessarily. But proposed land-transfer legislation in various states, including Nevada, Idaho and Montana, is tailored to the specific demographics, resources, and politics of those states. As a sovereign state, Colorado should have the right to formulate plans that benefit our environment, economy, and people.

The contentious Bureau of Land Management planning model, 2.0, actually limits local input and expands the ability of out-of-state special interests to have a say in public lands planning. This poke in the eye to local leaders is another example of why federal management is becoming more onerous, unfair and unpopular.

The EPA-caused spill of millions of gallons of toxic waste water into the beautiful Animas River in August of last year brought attention to the problematic nature of federal control and policies over local lands and resources. The seeming lack—or very slow in coming—accountability for those responsible has fanned the flames of discontent with federal agencies. As Western Colorado struggles with declining job prospects in domestic energy, restrictions on use and access to public lands, and environmental destruction caused by the federal agencies charged with its protection, the debate over who should manage public lands will continue to grow.

Although land transfer proposals don’t address the Antiquities Act, or the plight of the grassroots Navajo and other locals of San Juan County, Utah, their growing popularity in state legislatures, and the appearance of many new organizations promoting the transfer of public lands, is a signal that states and localities are no longer easy prey, to be gobbled up unnoticed, by the federal government.

Comments

Comments are closed.