Unloading cattle at facilities midway along a long haul has the possibility to cross contaminate with other cattle. This poses a major health risk for the animals and a biosecurity risk to the food supply. Hilker believes price discounts for long-transported cattle might occur in certain areas of the country and the costs of the transportation regulation will likely be passed onto consumers buying beef.

Wyatt Bechtel

Transporting cattle could become much more difficult if a set of congressionally mandated trucking rules go into effect before the end of the year. The regulations have the potential to cause devastating disruptions in how cattle are hauled, creating unintended biosecurity hazards and animal welfare issues.

On Dec. 18, 2017, the federal Electronic Logging Device (ELD) rule regulated by the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) will begin for commercial motor vehicles. ELDs are a record keeping device synchronized to a truck engine that logs information digitally. In real-time an ELD records data such as time spent on the road, miles driven, location and engine hours.

Use of ELDs is being enforced by DOT’s Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) through a mandate called MAP-21 which was signed into law on July 6, 2012. The regulations were supposed to create safer driving conditions and help eliminate the need for paper logs. Unfortunately, lawmakers didn’t consider what the changes might mean for livestock haulers.

Impact on Trucking and Producers

Steve Hilker, owner of Steve Hilker Trucking Inc., in Cimarron, Kan., could see what it would mean for his business when the regulations were first being established. The voluntary introductory phase for ELDs began Dec. 16, 2015.

“This is going to be a disaster for livestock transportation for anything over 500 miles,” Hilker says.

He isn’t opposed to using electronic logging, it is the hours of service limitations that come with the regulation that he disagrees with.

Under the ELD rule, truckers have an hours of service limit of 11 hours of driving in a 24 hour period. Drivers can be on-duty a total of 14 hours consecutively, including the 11 hours of drive time. After 11 hours are reached, drivers must rest and be off -duty for 10 consecutive hours.

“There has never been any consideration for a living, breathing cargo,” Hilker says.

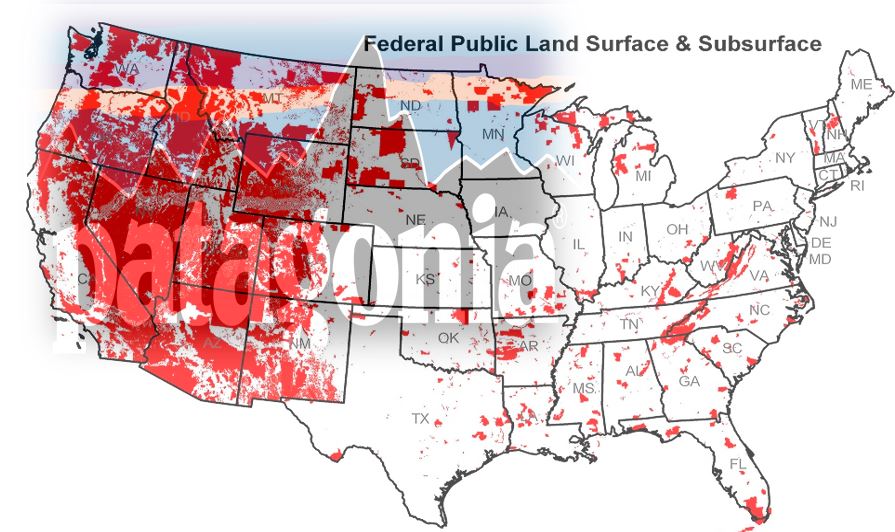

For long hauls, such as bringing calves from Florida or California to the cattle feeding region in the High Plains, it could be detrimental.

Individual drivers have two options after driving 11 hours, Hilker says. Either they park the truck and trailer or they unload the cattle. In both situations they would need to wait the required 10 hours before getting back on the road.

A study from Canada showed spending more time in a trailer causes additional shrink for cattle. From 10 to 20 hours in a trailer, cattle will lose 6% to 7.5% in body fluid. At 24 to 28 hours, cattle will start to lose tissue, setting their performance back before reaching a final destination.

Unloading cattle at facilities midway along a long haul has the possibility to cross contaminate with other cattle. This poses a major health risk for the animals and a biosecurity risk to the food supply.

Hilker believes price discounts for long-transported cattle might occur in certain areas of the country and the costs of the transportation regulation will likely be passed onto consumers buying beef.

“What will happen for the producer who is hauling here (the High Plains’ cattle feeding region) from Wyoming, Montana, Florida, Georgia, anywhere over 11 hours? They’re going to get paid less for their calves,” Hilker says. “The trucker is going to pass the cost on, we can’t absorb it.”

Another option would be to drive in shifts with an extra driver, but this will add additional costs and require more employees. There is already a shortage of truck drivers. In Hilker’s case, he has three trucks that are not running because there is a lack of available drivers.

Exemptions Exist

Agriculture exemptions do exist, but those exemptions literally don’t go far enough.

If an agriculture driver stays within 150 miles of the origin of their load the hours of service rule does not apply. A driver can go outside of that 150 mile radius eight days out of a rolling 30 day period.

Hilker plans to run his 16 livestock rigs without ELDs and stick to hauling cattle in his immediate area. A lot of local cattle transport occurs in his area, as he is situated between major packing plants in Dodge City, Garden City and Liberal, Kan., several feedlots near those towns and two large sale barns at Dodge City and Pratt, Kan.

“Because of where I’m at geographically I think I can make that work for my business. It is going to require more management on my part,” Hilker adds.

Paper logs are still required under the exemption and Hilker will need to monitor distances traveled to stay in the 150-mile limit.

Without an ELD attached to the trucks and operating under the MAP- 21 agriculture exemption, Hilker is losing a portion of his business that helped build the company. Starting out more than 30 years ago he often hauled cattle long distance from areas like the Northern Plains, Southeast and West into the surrounding cattle feeding region.

Another truck owned by Hilker is used for grain hauling in the local area so it will fall under the agriculture exemption, too. The 18th truck in his fleet is utilized for fuel hauling and will be the only vehicle equipped with an ELD.

Running an ELD can be costly depending on the type of unit purchased. Prices range from $285 to $1,000 per unit with an additional monthly service fee of $30 to $50.

“The thing about the ELD is none of them have been certified by the FMCSA. They allow the ELD manufactures to self-certify that they are compliant,” Hilker says.

Another reason Hilker doesn’t plan to install ELDs in his livestock hauling fleet is because none of the units he has looked at are also compatible with the MAP-21 agriculture exemption, which would be the majority of his hauls.

[paypal_donation_button]

Free Range Report

[wp_ad_camp_3]

[wp_ad_camp_2]